Girls’ education is a basic human right and a critical lever to reaching international development objectives. Education for girls helps break the cycle of poverty, makes them less likely to die in childbirth, and makes them more likely to have healthy babies. And educated women are, in turn, more likely to send their children to school. When all children have access to a quality education rooted in human rights and gender equality, it creates a ripple effect of opportunity that influences generations to come. As we approach International Women’s Day, it is important to highlight the work that donors and organizations around the world are doing to help girls learn.

In March 2015, then-President Barack Obama and First Lady Michelle Obama joined the fight to improve educational opportunities for girls around the world. Their Let Girls Learn initiative aims to help raise awareness and promote improvements in girls’ education. The Obamas join many others, including activist Malala Yousafzai, New York Times columnist Nicholas Kristof, and the creators of the 2013 documentary Girl Rising in supporting girls’ education. These calls to action build on the momentum started by several funders, including the Millennium Challenge Corporation, USAID, the World Bank, and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, all of which have been supporting girls’ education for many years.

Although education has dramatically improved in many developing countries, girls have not benefited proportionately from the improvements. Today, 62 million girls worldwide are still not in school, compared with 59 million boys. Barriers to education disproportionately affect girls. When poor families cannot afford to educate all of their children, parents often choose to enroll boys because they are seen as the future breadwinners for the family. Girls are made to stay at home and help with household chores such as cooking, caring for siblings, or fetching water. In some countries, parents have greater incentives to prepare their daughters for marriage than to send them to school because of financial gains.

Even when parents do enroll their girls in school, they still face risks and barriers. Many girls must travel long distances to get to school. In the most extreme cases, some girls face the risk of being raped or assaulted along the way. Within their schools, some girls face sexual discrimination and assault by their male teachers. Schools in developing countries often lack adequate sanitation facilities and privacy, which leads older girls to miss school for menstrual hygiene reasons. These absences cause them to fall further behind their male counterparts. Given these difficult and sometimes harrowing realities, the challenge of enrolling and retaining girls in school remains dire.

So what more can we do? Researchers at Mathematica Policy Research are part of the solution to these pressing problems. We assess the effectiveness of policies and programs to improve schooling and learning outcomes for children—especially girls—around the world. Our researchers focus on education interventions in dozens of developing countries.

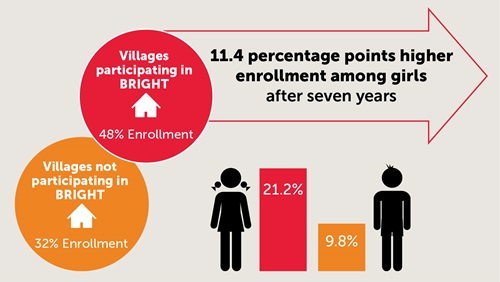

We have helped to develop gender mainstreaming strategies that enabled students to benefit from donor interventions equally; our reviews of social and gender issues in Bangladesh, the Kyrgyz Republic, Macedonia, Nigeria, and Norway integrated gender and human rights-based approaches and practices into counter-trafficking strategies and programming. In Niger, we helped to tackle the challenges of water, sanitation, and hygiene to help keep girls in school. We evaluated the impact of the Millennium Challenge Corporation’s IMAGINE program that constructed new schools with high quality infrastructure. The infrastructure improvements included on-site housing for female teachers and separate toilet facilities for girls and boys. Although the program affected boys as well, the resulting increase in girls’ enrollment was double compared with boys, and it positively impacted exam scores among girls.

Our experience assessing a similar program in Burkina Faso tells the same story—programs such as these increase the supply of education, support improvements in overall quality by using a gender lens to solve barriers affecting girls’ enrollment and retention, and in the end, lead to higher returns for the entire population. In Latin America, a performance evaluation of the Nicaragua Community Action for Reading and Security program found that the Espacios para Crecer (or Spaces to Grow) program improved how boys and girls treated one another in school. A representative from a nongovernmental organization noted that boys and girls treated one another with more respect and tended to have more positive interactions in the classroom because of the program. The evaluation also noted that girls and boys demonstrated similar results on reading tests.

The small steps that organizations are taking—and that our research contributes to—are important. Although gender equality does not mean that men and women are the same, the opportunities presented to girls and boys should not depend on their gender. Education can, and should, play a role in shaping attitudes and transforming behaviors to improve gender equity. Initiatives such as Let Girls Learn, investments by donors and foundations, and the research and evaluation work to assess the impact of these programs have all contributed to a better life for everyone.