On average, almost 130 people in the United States die from an opioid overdose each day, with the epidemic spanning rural and urban areas alike and costing the nation more than $78 billion each year. To address the breadth and complexity of substance abuse, a more comprehensive monitoring strategy is necessary—one that goes beyond siloed approaches focused on individual drugs or interventions. Last year, Mathematica worked with researchers at Montana State University (MSU) to help assess the policy value of municipal wastewater testing, an innovative approach that can augment existing data by providing more rapid, cost-effective, and unbiased measures of drug use. By analyzing wastewater data alongside data from existing local sources, we were able to assess policing impact on community drug use, when and where overdoses might occur, and black-market drug activity.

Wastewater can be a timely and objective source of data for making policy and program decisions. Wastewater is a combination of household sewage, industrial runoff, and, in some locations, storm water. The sewer captures wastewater from 81 percent of U.S. households, missing only those served by septic systems. Because wastewater from different pipes combines before ultimately ending up at a centralized treatment plant, the resulting data are identity-blind and not plagued by privacy concerns typical of medical data.

At the treatment plant, wastewater samples (typically 24-hour composites) are collected, then sent to a lab for chemical analysis. Concentrations of drugs in the sample are then translated to an average dose per person in the service area. Importantly, it’s possible to distinguish between drugs that were simply flushed and those that were actually ingested.

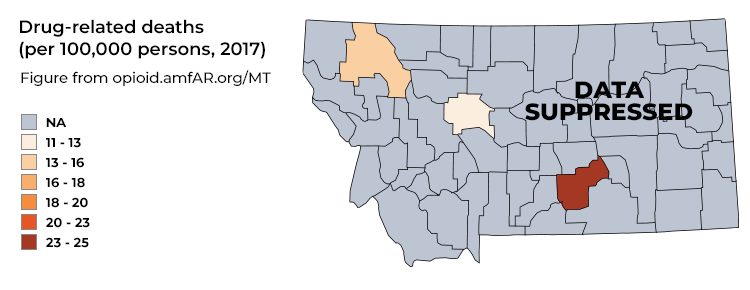

Although municipal wastewater testing is useful in rural and urban communities, the study in Montana underscores the particular value of this testing in rural areas, which tend to have more limited addiction treatment resources and less available data on population substance use. As indicated in Figure 1, county-level estimates of drug-related deaths in Montana are virtually all greyed out; the data are not publicly shared to protect individuals’ identities because deaths are relatively rare and Montana is fairly sparsely populated.

Figure 1: Data Inadequacy in Rural Communities

Between April and June of last year, MSU researchers worked with local partners to collect weekly samples of wastewater from two Montana sites—one urban and one rural. These samples covered between one-third and one-half of each county’s population (Table 1), and lab analysis targeted 18 compounds, ranging from opioids to stimulants to antidepressants. Mathematica compared estimates of drug use (based on wastewater data) with data on drug seizures by law enforcement, calls to emergency medical services (EMS) for drug overdoses, and pharmacy prescriptions filled.

Table 1: Montana Pilot Study Data

| Data source | Unit of measurement | Coverage per unit |

|---|---|---|

| Law enforcement | Drug seizure | 1 – 250 people |

| Emergency medical services | Overdose call | 1 person |

| Pharmacy | Prescription | 1 person |

| Wastewater treatment plant | Wastewater sample | Thousands of people - 42% of urban county - 33% of rural county |

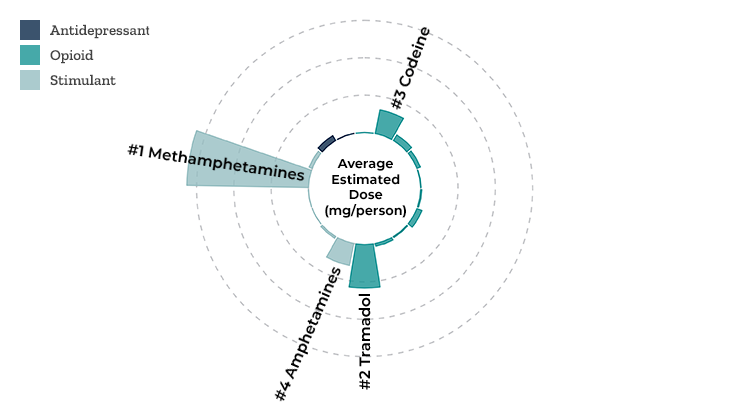

When we compared the profiles of drug use between the urban and rural sites, we saw that the most commonly used drugs were the same in both places—codeine, tramadol, amphetamines, and methamphetamines. But meth use was more than six to seven times higher in the rural site than the urban site (Figure 2). These findings point to the need to flexibly tailor funding, addiction treatment, and other resources to the substances that are spiking in the community.

Figure 2: Profile of Drug Use in a Rural Montana Site

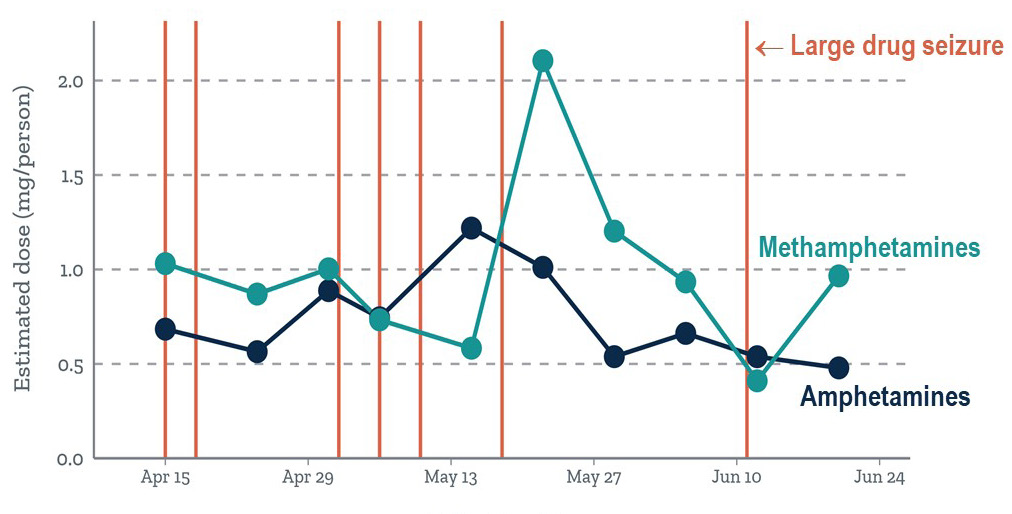

When we overlaid the timing of large seizures of amphetamines or methamphetamines made by law enforcement in the urban site onto graphs of wastewater-based trends in drug use, we could clearly see the effect that each major drug seizure had on community drug use. After every major seizure, community use of methamphetamines, amphetamines, or both decreased (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Wastewater vs. Police Data – Impact of Drug Seizures

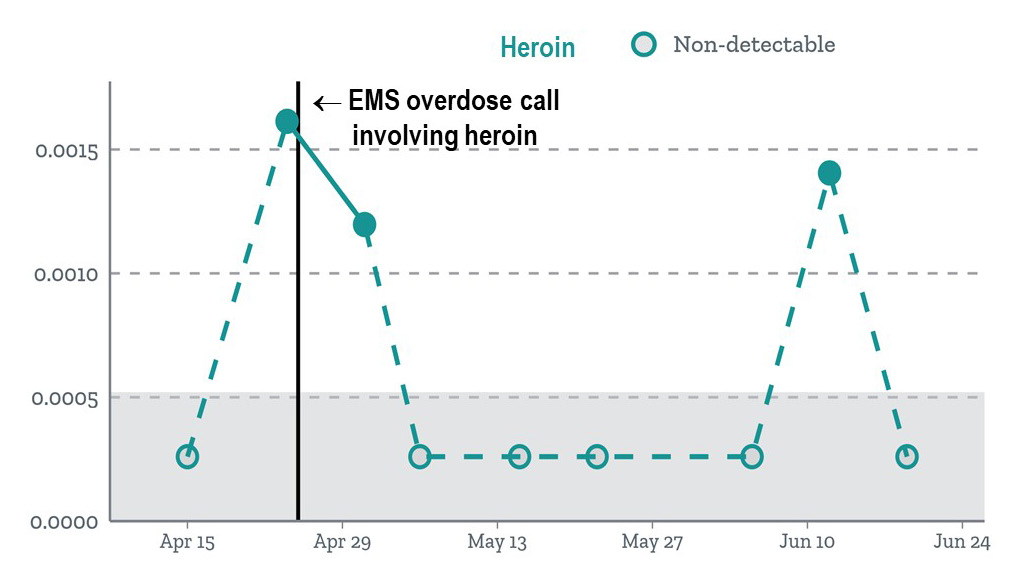

When we analyzed the timing of calls placed to EMS, we found that calls for overdoses involving a particular drug generally surfaced after wastewater data estimated high levels of use of that drug in the community (Figure 4). The pattern held up across both sites and for most drugs, even when many of our wastewater samples had concentrations of a drug that were too small to reliably detect—as was the case with heroin.

Figure 4: Wastewater vs. EMS Data – Predicting Calls for Overdoses

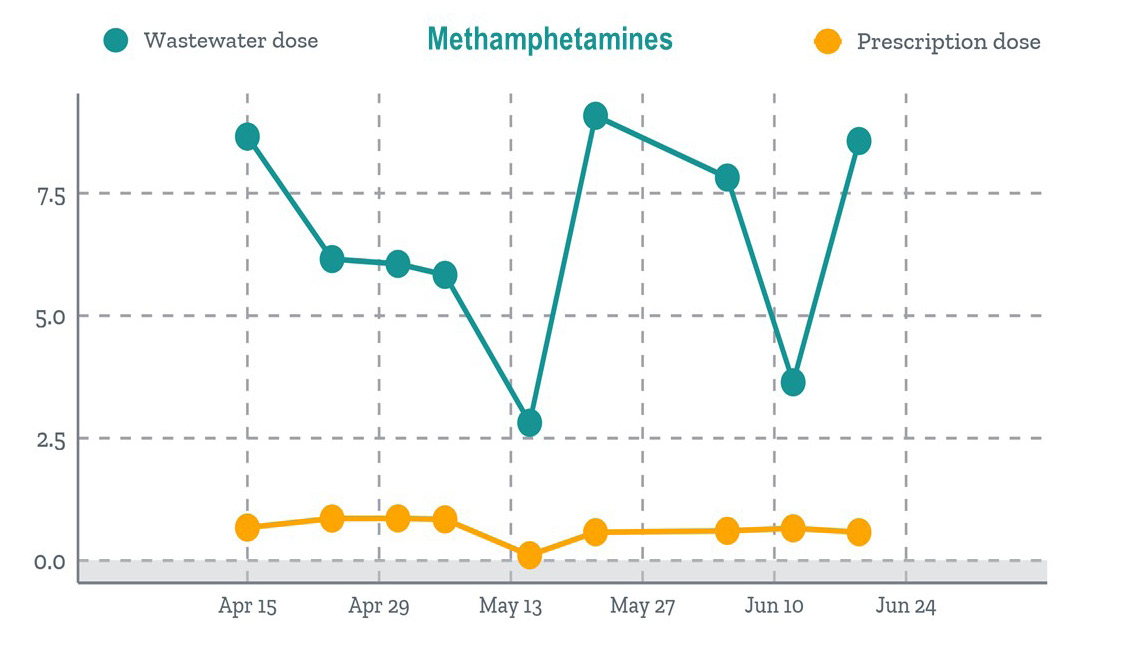

Finally, when we compared trends in doses excreted into the wastewater with the trends in doses of a prescription drug filled at one of two pharmacies operating within the rural site, the wastewater data suggested much higher use of methamphetamines in the community than the pharmacy data (Figure 5), shedding light on the extent of black-market meth use.

Figure 5: Wastewater vs. Pharmacy Data – Insights into Black-Market Use

The level of detail in wastewater data has great value for policymakers (Figure 6). Today, wastewater testing is routinely used across Europe as part of a holistic monitoring and alert system, as well as by the Australian Criminal Intelligence Commission to assess operational priorities. In the future, wastewater can be used for much more than monitoring drug epidemics to assess infectious disease outbreaks—including COVID-19, vaccine coverage, chronic disease prevalence, and medication compliance. Ultimately, tapping into a stream of data that’s already flowing continuously beneath our feet can provide a window into the health of our communities and can help stem public health issues before they explode into crises or even pandemics.

Figure 6: Multifaceted Policy Uses

|

|

Snapshots of the mix of drugs used provides an early warning on new drug threats |

|

|

Trends in drug use over time can be used to evaluate program effectiveness |

|

|

Hotspots of drug use inform a data-driven strategy to target resources |

|

|

Value of unbiased, scalable community health measures for policymaking |

The findings discussed in this blog stem from a multisite wastewater pilot study led by Dr. Deborah Keil and Miranda Margetts and funded through MSU’s American Indian/Alaska Native Clinical and Translational Research Program—a joint partnership with the National Institutes of Health to explore the health disparities in Native American communities in Alaska and Montana.