If there was any remaining skepticism about technology’s growing role as a catalyst for advancements in data science and social science, the COVID-19 pandemic should put an end to that.

The speed with which our public health systems have been tested by the spread of the virus, and the scale of the coordination required for a truly global response, has highlighted just how interconnected our world has become. Even beyond the devastating loss of life, the pandemic has also brought to the surface previously unacknowledged limitations of our information infrastructure and the systems in place for people to access critical social services.

When millions of workers who were laid off because of social-distancing guidelines can’t file unemployment insurance (UI) claims because of aging infrastructure (and the aging workforce to support it), that’s a problem. When children who rely on free and reduced-price school lunch programs are unsure when their next meal will come because schools are suddenly closed, that’s a problem. When those same kids and their classmates are suddenly expected to switch to distance learning without clear guidance on what that means and how to do it well, that’s a problem.

Tackling complex problems requires a combination of technology and science, and that’s been central to Mathematica’s work since our founding. In the same way that it was critical to embrace the technology of 50 years ago that enabled us to bring our econometric methods to life, now we need to embrace cutting-edge technology in order to develop tools and methods to better understand and more quickly address the world’s most pressing social challenges.

For instance, let’s look at the unprecedented changes that we’re seeing in the labor market as a result of closures related to COVID-19. In the last nine weeks, more than 38 million people have filed initial UI claims. We know this because the state agencies responsible for handling those claims report that information on a weekly basis. Those numbers are unprecedented, and they are often used to help paint a picture about what is happening more broadly within the labor market and the economy. But those numbers also don’t tell us the complete story. They don’t tell us about all the people who tried to file a claim but couldn’t get through because of outdated online systems and overrun phone lines. They likely don’t tell us about many of the workers in the so-called gig economy who traditionally haven’t been eligible for UI and might not know that new rules now allow them to apply. And they don’t tell us what’s happening this week, let alone what might happen next.

These traditional data sources give us a traditional view into the challenges our country will face when it is safe to transition to a more “normal” work routine. By default, these data sources also lead to traditional policy approaches. But by applying technology at the intersection of data science and social science, we can prepare policymakers with the tools they need to make more informed decisions about how to move forward.

That doesn’t mean abandoning our commitment to rigor and objectivity in search of an easy fix or a tech-enabled silver bullet. But it does mean rethinking the entire range of tasks we’ve been asked to do as researchers and analysts.

We need to identify data that we can use effectively. We need to collect, manage, and process those data. We need to use those data in a thoughtful analysis. And ultimately, we need to get those data into the hands of the people who need it most.

These tenets have been the bedrock of our approach and the foundation for our methods for years, and the need for this approach isn’t going anywhere. What is changing is that every step of that process is being transformed by technology as it enables researchers and policymakers to capitalize on the benefits that data can bring.

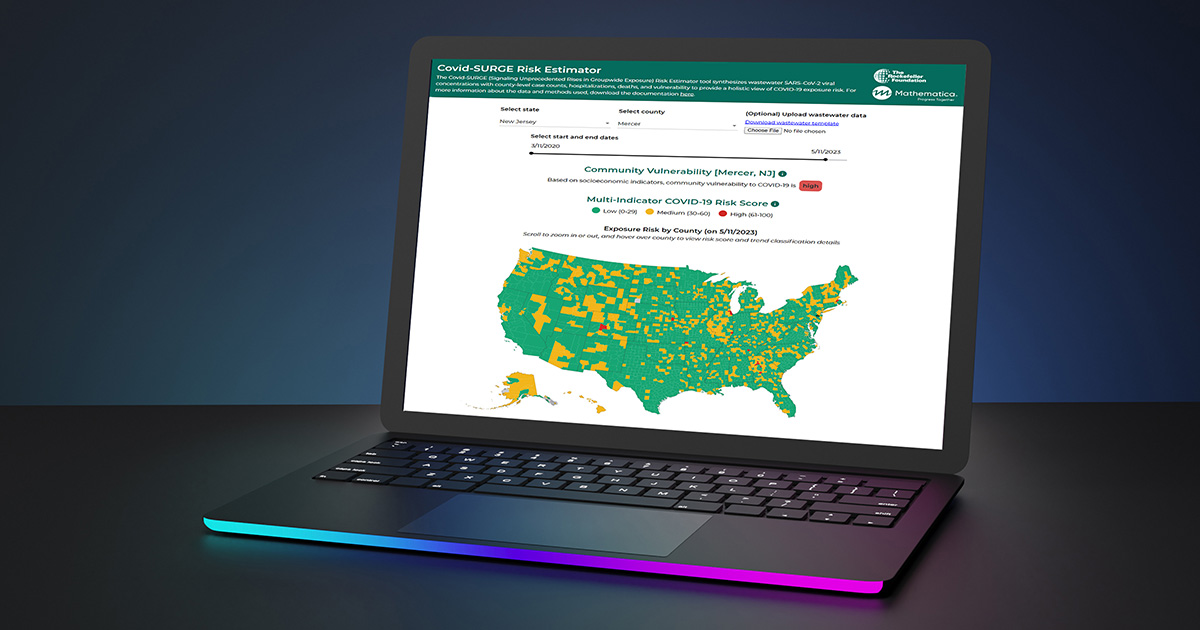

That means being open to tapping new sources of data like online job postings, keyword searches, restaurant reservations (remember those?), and metrics on energy consumption that can give an early look at problematic trends. That means rethinking how to manage and process administrative data like UI claims to translate the data into a more powerful tool for effective policymaking. It also means reimagining how policy audiences will want to consume research and analysis and working to get it in their hands the way they need it, when they need it. We’ve seen the power of this approach already with a number of tools, including a curated list of COVID-19 data and policy resources and 19 and Me—an online COVID-19 risk calculator developed during a recent Mathematica hackathon.

With technology at the center of new approaches that pull from both data science and social science, decisions can rest on a far more rigorous body of research, with much greater reliability. We can not only demonstrate the evidence, but also measure it, which can help determine how much to let enthusiasm or concerns about specific approaches guide policy.

That level of rigor and reliability is critical as the entire evidence community looks to fulfill the promise of evidence-based policymaking. And as we do so, technology is going to be at the heart of Mathematica’s efforts to deliver on our mission to improve public well-being in ever more meaningful ways. Today’s complex challenges require it.