Policymakers, policy advocates, and other stakeholders have explored many strategies to reduce spending on American health care, yet spending remains among the highest in the world, without higher performance on many key indicators. Although high disease burden and high use of expensive medical technologies are important drivers, many also point to high prices within the private sector as an important factor in health care spending. One lever that hasn’t yet been exploited broadly is price transparency—readily available information on the price of health care services that, together with other information, helps define the value of those services and enables patients and other care purchasers to identify, compare, and choose providers. This lever’s potential power stems from the fact that health plans and their insured customers, as well as self-pay patients, face widely disparate prices for the same service from different providers—and higher provider price often does not represent higher quality. At least in theory, shining a light on prices and supplying quality information should drive overpriced providers to reduce their prices or lose business.

Now is an especially good time to think about the role price transparency could play in “moving the dial” on health care spending. A new federal rule on price transparency requiring hospitals to share their negotiated prices for shoppable services is set to take effect next month. Another rule requiring health plans to provide specific negotiated rates and consumer cost-sharing information broken down by service is set to begin to take effect one year later. Greater transparency could enable consumers to shop in more price-conscious ways or could shift the arrangements between health plans, hospitals, other providers, and consumers in ways that result in lower spending.

The rules could change market dynamics across the country, but the ultimate effects are not clear.

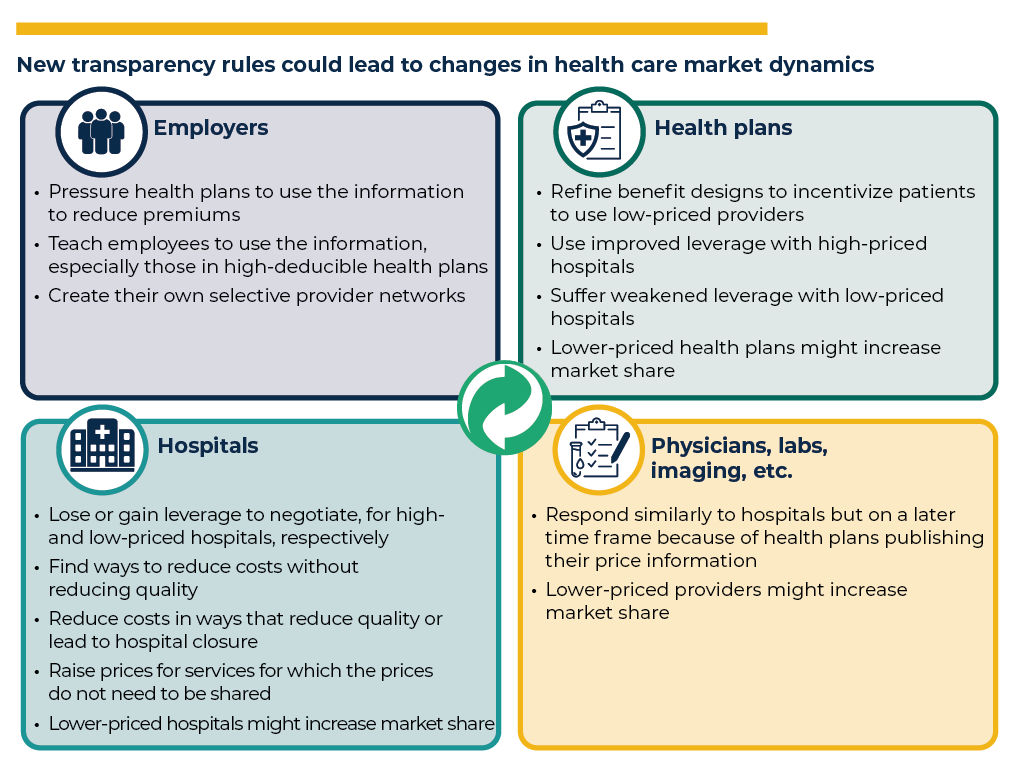

Because information is power, revealing price information has the potential to change the dynamics between employers, health plans, hospitals, and other health care providers. Because health care is a complex system, it’s uncertain how and how much these dynamics will change, and whether the result will be lower costs for consumers without reduced quality. That said, we have listed several potential effects in the following figure. Further, the effects of the new rules are likely to vary across markets. The affected organizations within each market differ in their strategies and relative market power, and the consumer populations also vary in their needs and preferences. The new rules will not affect what Original Medicare pays providers because Original Medicare sets payment rather than negotiates rates; the rules will also not affect what state Medicaid fee-for-service programs decide to pay providers.

The rules are controversial.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services characterizes the rules as an important victory for consumers. Supporters include Healthcare Bluebook and the ERISA Industry Committee (representing many large employers), as well as some influential researchers.

However, hospitals and health plans/insurers oppose the new rule, with the American Hospital Association’s lawsuit against the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) pending in the U.S. Court of Appeals after it lost a lower court ruling in June 2020.

Industry members and others have expressed concerns about the content of the rules, but the evidence points to a more nuanced story.

Will consumers be interested in using the information?

On one hand, consumers have not used price comparison tools much in past initiatives. Typically, patients obtain care from wherever their physician suggests, with one study showing that patients drove by an average of six lower-priced options to get a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan from their physician-recommended location. Historically, insured patients have been shielded from most health care costs at the time of service through their health plans. Instead, they bear high costs indirectly through premiums.

However, in recent years, at least two surveys show consumers are interested in learning about health care prices. Also, high-deductible health plans have become more prevalent, exposing consumers to more costs, which has been shown to be associated with greater use of price-shopping tools. If the rules work, market dynamics could also benefit consumers by resulting in lower prices, even if consumers do not use the information directly.

Will consumers be able to use the information?

The current hospital or health plan rules don’t make direct cross-provider and cross-plan comparisons, which would be one of the easiest ways for consumers to use this information. However, tool developers and others, such as self-insured employers, can use the required machine-readable files to create cross-provider and cross-plan comparisons.

Will consumers be misled by using price information without corresponding quality information?

Consumers have been known to mistake high prices for high quality, as with other consumer goods. Quality information for providers exists separately, is incomplete, and does not correspond with many of the listed services. The new rules could spur efforts to develop more aligned quality measures, and well-designed tools could properly align price and quality information.

Could the rules result in upward rather than downward price pressure?

Health plans attempt to negotiate lower prices from providers and, in some cases, they have been quite successful. In these cases, exposing results of health plan negotiations could undermine that success when those providers learn that others are being paid more. At least once, an insurer dropped a price transparency initiative after provider pressure to raise payment rates. Others believe health plans will use the information to apply downward price pressure to high-priced providers. Multiple examples exist of successful cost reduction following price transparency initiatives, documented through a study of state price transparency websites, a study of the experience of 18 employers that used a price transparency platform, an evaluation of an insurer-led initiative, and a study of another large employer initiative.

The price transparency rules will not be a silver bullet for health care cost reduction. The new rules are just a starting point. Implementation could fail in various ways, the first of which is a court ruling adverse to HHS.

Despite concerns, there are reasons to be optimistic.

Several prior smaller-scale price transparency initiatives or studies demonstrate reduced spending and shifted dynamics in ways that benefit consumers. For example, the cost of hip replacements was found to decrease by 7.3 percent in states with websites that shared prices, with about half of the decrease estimated to come from providers reducing prices and about half from consumers switching to less expensive hospitals. An insurer-led initiative focused on informing patients who had had an MRI about MRI imaging costs found an 18.7 percent decrease in cost to the insurer of subsequent tests, and the variation in prices among affected providers shrunk by 30 percent.

In addition, several key trends could help the rules have a greater effect now than in the past. More consumers are participating in high-deductible health plans, where their attention to price can directly affect their personal spending. As providers have begun participating in alternative payment models (APMs) more frequently, they could become more interested in price information because it might affect their bottom line under the risk arrangements that APMs introduce. Meanwhile, we’re also seeing innovation in new digital solutions that could use the price data to create customer-friendly comparative tools, making it potentially much easier for consumers to use the newly available information when planning their health care.

Given the importance of reducing health care spending, policymakers should study the implementation and consequences of the transparency rules beginning after the first year, and they should remain ready to make timely adjustments if adverse effects emerge. In 2022, key research questions include whether the highest-priced hospitals as of early 2021 reduced their prices by early 2022, without apparent reduction to quality or access; whether employers report using the information to pressure health plans to create more cost-effective networks; and whether consumers in high-deductible plans used the information. Being ready to understand this early experience with the hospital rules might help us identify lessons that could be used to ensure effective implementation of the broader transparency rules for health plans set to take effect during 2022-2023.