In most parts of the country, your local tax dollars funnel into government programs and services the same way they have for generations: as marginal spending increases or decreases based on what your city, county, or state spent the year before. In his new book, author Andrew Kleine argues that local governments are doing it wrong. Instead, he writes, communities should invest in long-term strategic outcomes based on community priorities, and tax dollars should flow to programs aligned with those priorities that demonstrate results. To invest in programs that demonstrate results, he says, local governments must measure progress with objective and timely data.

In most parts of the country, your local tax dollars funnel into government programs and services the same way they have for generations: as marginal spending increases or decreases based on what your city, county, or state spent the year before. In his new book, author Andrew Kleine argues that local governments are doing it wrong. Instead, he writes, communities should invest in long-term strategic outcomes based on community priorities, and tax dollars should flow to programs aligned with those priorities that demonstrate results. To invest in programs that demonstrate results, he says, local governments must measure progress with objective and timely data.

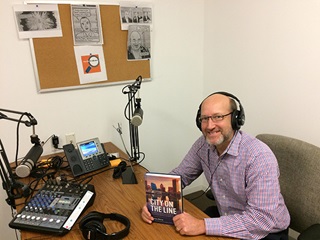

Kleine lays out his ideas in City on the Line: How Baltimore Transformed Its Budget to Beat the Great Recession and Deliver Outcomes, which covers his decade-long tenure as Baltimore’s budget director and what he learned along the way. In late October, Kleine spoke with Mathematica’s J.B. Wogan and Matt Stagner about the book. Since the interview, Kleine became the chief administrative officer for Montgomery County, Maryland.

You can read an edited excerpt of the interview in the following transcript.

Why did you decide to write the book, and why now?

I started writing the book in 2016 while I was still budget director for the city of Baltimore. We had been running outcome budgeting for several years in the city. Other cities were trying to visit us, flying us to visit them, and wanting to learn more about what we were doing. Clearly there was an interest among cities in changing the way they budget. So that was one motivation for me.

Another had to do with the city of Baltimore itself. I was there for 10 years, and I think that that was one of the most tumultuous decades in the city’s history outside of wartime. I was hired by a mayor who resigned in a political scandal. I arrived just in time to grapple with the Great Recession. And in 2015, many of the listeners will know about the civil unrest in Baltimore after the death of Freddie Gray. What followed after that was a huge spike in violent crime. It just felt like there was a lot of bad news about Baltimore, and this is a tiny bit of good news that I wanted to let people know about.

What is outcome budgeting?

I like to define outcome budgeting in contrast to the traditional budget process that it replaces. In traditional budgeting, the starting point is what you spent the year before. That’s your base budget and it changes only incrementally. With outcome budgeting, you’re looking forward instead of backward. When Mayor Sheila Dixon interviewed me for the job, she said, “The budget is a black box to me. Ninety-nine percent of it seems to be on autopilot.” I think that’s true in a lot of cities. The base budget just sort of moves forward like a glacier. It’s layers of decisions made over many decades and no one’s digging down to see what’s inside of that black box. In outcome budgeting, your starting point—instead of looking at what you spent the year before—is looking at what you’re trying to accomplish in the future, what outcomes you want to achieve for the community and how you are measuring those.

Would you give an example of one outcome that improved over your time in Baltimore?

One that I’m proud of is the infant mortality rate. That was a case where there was some good work happening starting around the same time as outcome budgeting. It’s called B’More for Healthy Babies, and they were taking an approach of bringing together a lot of partners and establishing performance measures and tracking their progress.

The first year of outcome budgeting was one of worst years of the Great Recession in terms of its impact on the city’s finances. Even though we had to close a huge budget shortfall, by prioritizing our spending, we were actually able to increase funding for services that were demonstrating results. B’More for Healthy Babies was one of them. We did that by eliminating and reducing funding for services that weren’t doing so well. So one way outcome budgeting helped to promote better outcomes was by ensuring that we were providing resources to services that were demonstrating results.

Given that you can’t conduct a randomized controlled trial for every program or service, how did you try to measure impact? And as a follow-up question, how available and useful were the data that you got?

One of the big breakthroughs of outcome budgeting for Baltimore was that it finally got people focusing on outcomes and measuring outcomes. Baltimore was well known for being the birthplace of CitiStat, which is a program that gathers what I would call operational metrics on a weekly or even more frequent basis and reviews those with the relevant agencies to identify and address performance issues in real time. That’s an important function, but those measures are not looking at the long-term outcomes that we seek. You could be doing great on fixing potholes within 48 hours without making progress on the long-term condition of your roadways. That’s just a simple example where you can “win at CitiStat” without making progress toward the long-term outcomes that you want to achieve.

Orienting our thinking toward outcomes was a big change for Baltimore. Every service and city government under outcome budgeting had to have a set of performance measures including at least one outcome measure. I think we were able to spur interest in gathering more data, but honestly there’s not a lot of rigorous evaluation data in local government. When we started, it was a pretty new concept for a lot of people. We said to do the best you can. If a city service hadn’t been evaluated, an agency might look at evaluation data from similar services in other places, in other cities. They could look at academic literature. One example is our tree maintenance program. They wanted to make the case for investing in not just tree planting, but also keeping trees healthy, especially in their early years, to improve the tree mortality rate.

They showed us evidence of how trees reduce energy usage and even increase the lifespan of a neighborhood street—if it’s shaded, it doesn’t need to be resurfaced as frequently. So they showed us some cost-benefit analysis on that. Across the government, we were seeing data that we hadn’t seen before. It wasn’t perfect, but it was a lot better than what we had in front of us in budget processes of the past.

Whenever someone introduces an idea that seems like a common sense improvement on the status quo, I wonder about what it was about the old way that gave it such longevity and popularity. If you were to write up a pros-and-cons list for traditional budgeting, what would you put in the pro category? What is there to recommend it?

[Traditional budgeting is] a lot easier than outcome budgeting. It’s also more comfortable for political leaders because it’s easier when they’re dealing with agency heads or community advocates to say, look, it’s a tough budget, but we’re treating everybody the same across the board. We’re cutting the budget in order to get to balance. That’s a lot easier than having to explain why, based on data and evidence, we are spending less on your favorite program so we can spend more on a program that’s having more impact and is more aligned with our priorities. Part of that is, people don’t always want to accept data and evidence, and it’s more difficult to explain the data and evidence, so it’s easy to fall back on just treating everyone the same.

Most places don’t use outcome budgeting today. Looking 5 to 10 years into the future, do you think it will continue to be rare?

I hope not. You know, obviously one of the reasons I wrote the book was that I want to both inspire more cities to try it and also give them tools to do it that I didn’t have when I first started. I see more and more focus on data in local government. I want leaders to realize that it’s great to use data to solve problems, but ultimately the budget is the longest lever you have to really shape the priorities of local government and to impact communities. So let’s use those data to inform the budget process, and this is how you do it.

Want to hear more episodes of On the Evidence? Visit our podcast landing page or subscribe for future episodes on Apple Podcasts or SoundCloud.

Show Notes

Kleine, Andrew. City on the Line: How Baltimore Transformed Its Budget to Beat the Great Recession and Deliver Outcomes, Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2018.

Kleine, Andrew. “Turning Traditional Budgeting on Its Head.” Governing, Tuesday, October 9, 2018, Voices section.

Kleine, Andrew. “Investing in Your Employees' Best Ideas.” Route Fifty, Tuesday, October 30, Finance section.