The federal government and some states are increasingly looking toward work requirements in benefit programs as a way to increase employment among populations with limited income. We can learn useful lessons from federal programs that already require work, with the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program perhaps the most familiar and well studied.

But other federal programs also require work or work-related activities for some benefit recipients, including adults who do not have a disability nor dependents and receive government food aid through the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). States can also mandate that SNAP recipients participate in an employment and training program in order to maintain benefits, but many states operate voluntary programs or exempt most recipients, including parents.

Using demonstration projects, the federal government allows public housing authorities to impose work requirements for adult residents in some cities through the Housing and Urban Development’s (HUD) Moving to Work Demonstration (MTW) project. And most recently, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) approved waiver requests from nine states to require some Medicaid recipients to work or do community engagement, and six other requests are pending (as of April 1). A Washington, D.C., federal court judge recently struck down waivers that allowed Medicaid demonstration projects in Kentucky and Arkansas. However, CMS has appealed those rulings and other states remain undeterred in pursuing Medicaid work requirements.

As work requirements gain traction, research and experience offer key lessons for designing and implementing them. Three key questions to consider include the following: How effective are they?, How are work and exemptions defined?, and What services should be offered?

Effectiveness of work requirements. A number of literature reviews largely conclude that work requirements, in addition to other things, decreased Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC, the precursor to TANF) and TANF caseloads and increased employment for single mothers, although the post-TANF research explores a package of policies and not work requirements alone. Researchers interpret this literature in many ways; as such, it can be difficult to make broad statements about the effectiveness of work requirements in AFDC/TANF. Nonetheless, the literature shows that work requirements can reduce caseloads and increase employment when done well.

SNAP imposes a work requirement on recipients who do not have dependent children and are determined to be capable of work (the program calls them able-bodied adults without dependent children). They can only receive SNAP for three months in three years unless they are working or participating in an approved work activity. The literature on the effectiveness of SNAP work requirements is limited, largely due to methodological challenges associated with reliable data on SNAP receipt and on people who are and are not subject to the requirements. The few studies that attempt to address these data challenges find that SNAP work requirements reduce SNAP receipt among those they target, but are less clear on the employment effects. One study found that SNAP receipt more broadly reduces employment, suggesting that a work requirement could influence employment rates. Another suggested that SNAP work requirements do not affect employment at all.

When it comes to housing assistance, eight public housing authorities, through the HUD MTW project, require non-exempt public housing tenants to work. Similar to SNAP, little is known about their effectiveness given several limitations to evaluating them. But one study of MTW in Charlotte, North Carolina, suggested that work requirements had modest, but positive effects.

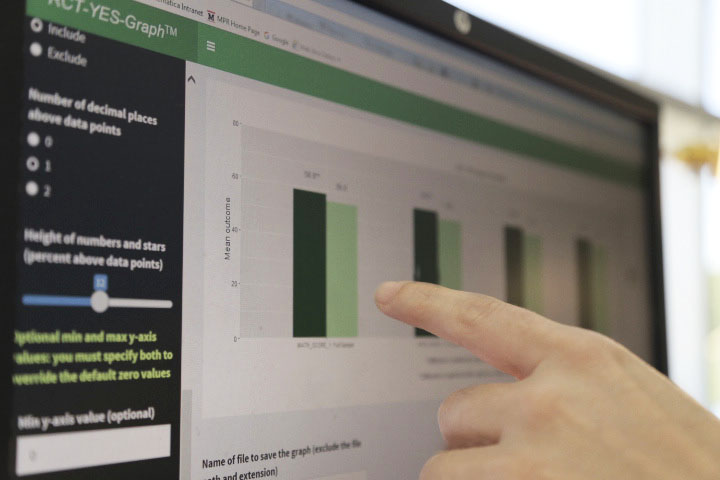

It is too early to evaluate Medicaid’s work and community engagement requirement waivers in the two states implementing them (Indiana and New Hampshire). With luck, this will change in time. CMS requires that waiver states evaluate the effectiveness of their efforts, and Mathematica recently released guidance to states on how to do it.

Regrettably, this means that little is known about work requirements outside of the context of TANF. More research is needed that tests them in the context of other benefit programs, with a particular focus on the role that implementation issues play, such as how the administering agency communicates requirements and decides exemptions, and how staff and recipients track and report hours.

Definition of work and exemptions. Policymakers must decide how to define work and who should be exempted from requirements. The TANF experience offers some important lessons. The federal government, in accordance with the TANF law, defines “work” as 12 activities, including 9 that count toward all hours of participation (called core activities) and 3 that count but in a more limited way (called non-core activities). Countable activities include things like subsidized employment, on-the-job training, community service, and job search or vocational education for a limited amount of months.

Allowing many activities to count as work in TANF provides states the flexibility to offer participants the services they might need. But a 2015 Mathematica report highlighted some of the challenges that states and participants face in counting hours, which can be particularly challenging because of the need to distinguish between core and non-core activities.

SNAP, the MTW housing demonstration projects, and the Medicaid waivers also use broad definitions of work to include job search, training, education, and community service, but they do not delineate between core and non-core activities. This might make work requirements easier to administer in these programs (without the core and non-core distinction), but participants and administering agencies must still keep track of total hours. Monitoring hours of work activity and communicating with benefit recipients can be challenging for states, as Arkansas learned before the federal court struck down its Medicaid work and community engagement requirement.

Exemptions are allowed across these programs for recipients who cannot be expected to work. These include by age (exempting children and older adults) and caregivers with no child care. These programs also exempt people who cannot work due to disability or another mental or physical health limitation. Staff from the administering agencies, typically state or local workers, must determine who is exempt and who is not according to federal and state guidelines.

In the TANF context, research shows that some states do a better job than others identifying issues that should exempt a participant from work requirements. For work requirements to be effective in other contexts, states must pay close attention to exemptions and provide clear guidelines to staff about when and for how long to exempt a participant.

Services. Work requirements have a better chance of increasing employment if they are paired with quality services. Research on the early AFDC demonstration projects from the 1980s and 1990s identify some key components of effective programs: having an employment focus, allowing participants to build basic skills, and using a mix of services. TANF is structured in a way that allows states flexibility to offer these types of services and employment supports.

But with SNAP, funding for employment services is more limited than for TANF. SNAP provides funding for employment and training programs (SNAP E&T), but sufficient resources are not available in most states to provide services to all who are eligible. And unlike TANF, we know little about what works in SNAP employment programming. Mathematica is currently conducting an evaluation of 10 SNAP E&T programs with results expected in 2021. This is the first comprehensive evaluation of SNAP E&T services.

For Medicaid, employment-related services are not an approved expenditure, meaning that states must use other workforce development funding (such as the Workforce Investment and Opportunity Act, TANF, or SNAP E&T for those who are dually enrolled). One concern about Medicaid work requirements is that not enough funding is available to provide employment-related services to participants subject to them.

Where does this leave work requirements in government benefit programs?

Increasingly, some policymakers are exploring ways to expand work requirements for SNAP and Medicaid. Evidence and experience demonstrate that they can be effective if implemented well. Understanding what has and has not been effective, carefully defining work and exemptions, and considering what services to offer and how to pay for them are good first steps for policymakers to consider. Mathematica is currently conducting a study for the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services that will describe how work requirements are implemented under TANF, SNAP, and public housing programs. Expected to conclude in the fall of 2019, this study will further inform this important debate.