One year ago, as pandemic lockdowns spread across the country, I watched a new documentary, The Trials of Gabriel Fernandez, released by Netflix as a six-part miniseries. Since the moment 8-year-old Gabriel’s face appeared on my screen, a day hasn’t gone by when I haven’t thought of him and the abuse and neglect he suffered. While Gabriel’s was an unusually extreme situation, for many he’s come to symbolize the hundreds of thousands of children reported to state child welfare agencies—and the many children who will come after him if we do not improve our prevention efforts. This post is not about the documentary series, which depicts deeply disturbing child maltreatment that ultimately led to Gabriel’s murder in 2013 or other extreme situations like Gabriel’s. This post is about recognizing that, while Gabriel’s life was taken so brutally, his memory might help other families and their children. Those of us who have the power to improve prevention programs and change policy owe it to Gabriel to try harder to identify the root causes of abuse and create action-oriented solutions.

To start, we can help government leaders, particularly those at the state level, make informed choices about investing in programs that help children at risk of maltreatment. For example, compelling evidence from Washington State demonstrates the efficacy of community-level public-private partnerships aiming to serve kids who are exposed to adverse childhood experiences. These experiences can include child abuse and neglect as well as exposure to household substance use, incarceration, or mental illness, which can negatively impact child development and behavior. According to the National Conference of State Legislatures, more than half of adults in 23 states across the United States reported having at least one adverse childhood experience. By implementing consortiums of public agencies, private foundations, and community organizations that use trauma-informed programs, policies, and practices, Washington has helped moderate the effects of adverse childhood experiences and reduce their related public and private costs.

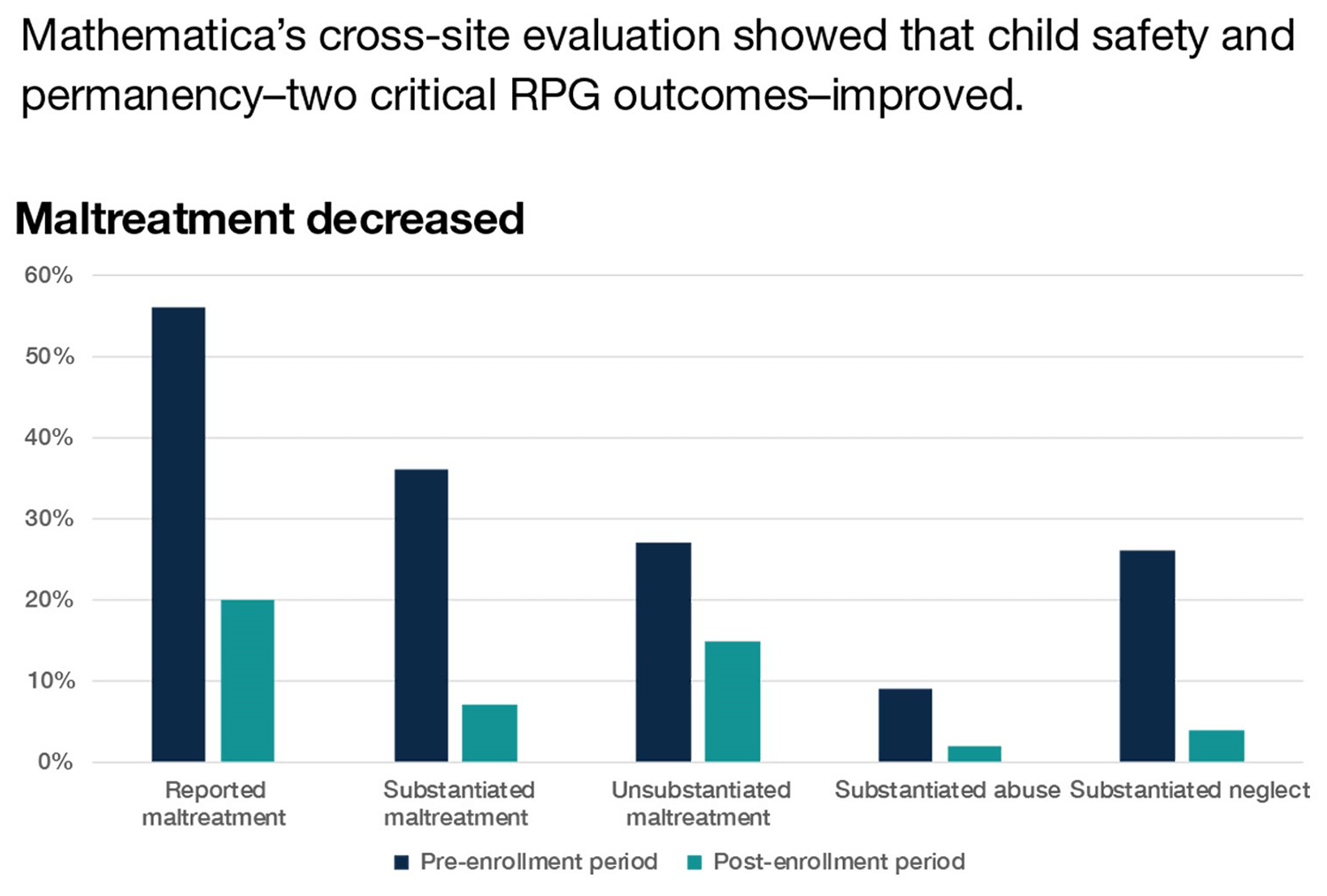

For many families, struggles with substance use disorders are at the heart of their challenges with caring for children. The Administration for Children and Families in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services administers the Regional Partnership Grants (RPGs) program, which funds partnerships between providers of child welfare services, substance abuse disorder treatment, and other social services that enhance the safety and well-being of children who are at risk of entering the child welfare system. New evidence shows that RPGs strengthened collaborations between providers and enabled more partnerships to use best practices for evidence-based programming, which led to improved outcomes. Our evaluation of 17 partnerships in 15 states shows that RPGs resulted in fewer episodes of maltreatment and removal of children from their homes, and other measures of children’s well-being largely improved or remained stable.

When the Family First Prevention Services Act (Family First) was signed into law in 2018, states gained potential access to more federal resources to target investments in prevention-based programming, including some mental health services, substance use disorder services, and parenting programs. Despite some progress toward better meeting families’ needs, there’s more work to do. Family First offers opportunities for states to receive some reimbursements for prevention services, but state leaders must develop evidence or use existing evidence-based programs, as well as think about the best ways to combine multiple funding mechanisms to pay for services and related supports for parents and children. Mathematica and the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation developed a new resource—Planning for Title IV-E Prevention: A Toolkit for States—that might help. The toolkit contains a blueprint for offering a comprehensive array of services designed to address the needs of families with children who are at risk for abuse and potential foster care placement. In addition, the toolkit includes questions and information to consider about the characteristics of state populations, the landscape of services and providers, and insurance coverage and funding.

One challenge is the great variation in state and local laws and regulations. In assessing how the system is doing in protecting children, we struggle to understand variation in how states define and respond to child abuse, neglect, and maltreatment. Although federal law establishes a common framework under which state child welfare systems operate, states and localities drive much of their own systems’ structure and complexity. A new data resource, known as the State Child Abuse & Neglect Policies Database, or SCAN Policies Database, is changing the way we analyze child welfare data to learn more about child maltreatment incidence across the United States. This free database makes it easier for researchers, analysts, policymakers, child welfare agencies, and others to understand how differences in state laws and policies might influence how states collect data and study rates of child abuse and neglect.

April is National Child Abuse Prevention Month. As we reflect on how much has changed in the last year and how much has stayed the same, I struggle knowing that many kids living in situations like Gabriel’s are worse off as a result of home quarantines and parental stress. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that the number of emergency department visits related to child abuse and neglect decreased during the pandemic, but the percentage of visits resulting in hospitalization increased, compared with 2019. As such, there's widespread concern about reduced reporting of child abuse and neglect to child welfare agencies during pandemic-related stay-at-home orders. Little is known, however, about the types of cases that are being reported during the pandemic and how child welfare agencies are responding to them. Insights from a June webinar with the Centre for Social Data Analytics and the Children’s Data Network shed light on using current data to deepen our understanding of the pandemic’s impact on child welfare screenings and referrals. Predictive risk scores, for example, can provide nuanced information about how child welfare reports have changed, and how those reports are being screened.

Now is the time to implement evidence-based approaches to address child abuse prevention and ensure that Gabriel Fernandez’s short life is never forgotten.