As researchers, program evaluators, and technical assistance providers, we’re often disconnected from the people we hope to impact through our work. It’s not ideal, but it’s possible to study a school without ever walking its hallways. It’s possible to evaluate an intervention without ever seeing it in action, or to deliver technical assistance without witnessing how a recipient puts it to use. But I believe what drives us at Mathematica is the desire to help people—to help individuals and communities solve meaningful problems. What drives me is the desire to help educators and schools improve academic opportunity and outcomes by addressing historic and systemic inequities.

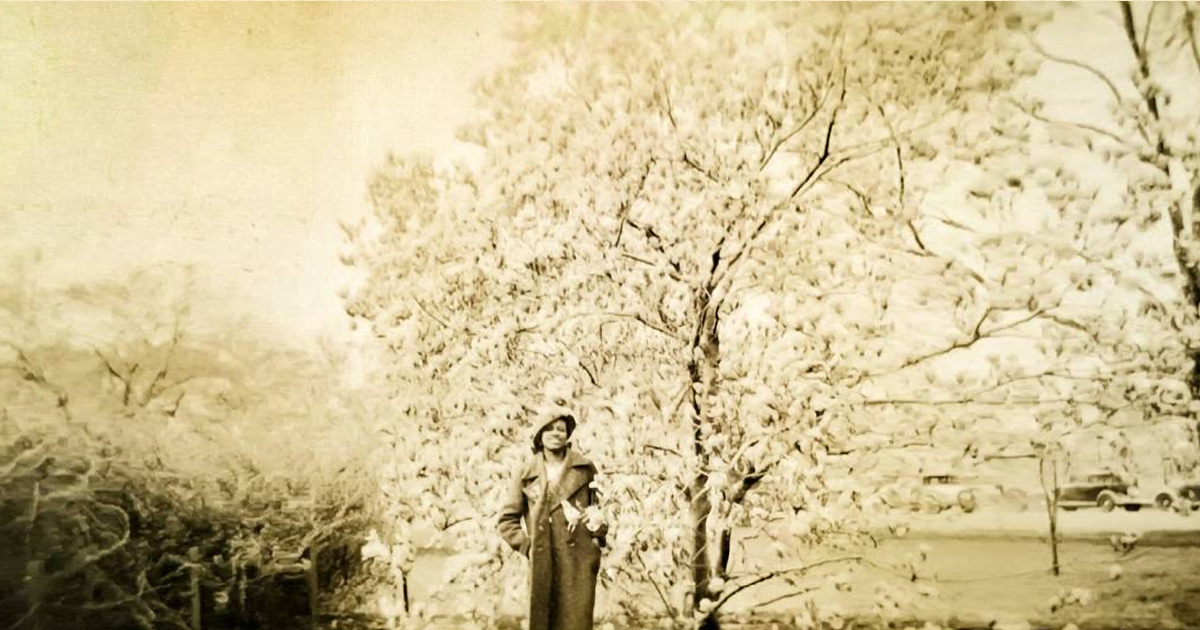

Education comes first in my family—even if it means living apart to pursue it. My great-grandparents viewed it as an antidote to life in the Jim Crow South. I’m a fourth-generation Washington, DC native. My grandmother and her siblings were the first to arrive, having been sent by my great-grandparents from Danville, Virginia to DC in the 1920s to attend Dunbar High School, the first public high school for black students in the United States. Later, they each attended Howard University for their undergraduate studies, and eventually attended other universities for graduate school. My grandmother earned a master’s degree and was a high school guidance counselor for most of her career. Her siblings earned medical and doctoral degrees. My grandfather, born an orphan, attended graduate school on the G.I. Bill after serving in World War II. He became a professor of insect physiology and ended his career as a teacher and researcher at Howard. My parents, aunts, and uncles followed the example of this generation. This heritage has granted me a life in which more doors have been opened than closed.

Particularly in the 1980s, it wasn’t possible to live in DC without recognizing that most kids who looked like me didn’t enjoy the same opportunities. I wanted to change that, so I contemplated a career in education. As a kid, I was just as likely to play “school” and develop (really good!) lesson plans as I was to hit the roller rink or pool with my neighborhood friends. I fully committed to the idea of teaching when I entered college. Ironically, a number of my relatives discouraged this decision. They believed that teaching was what educated people of color pursued when discrimination limited alternative professional pathways. They didn’t make financial sacrifices and suffer indignities and humiliation for me to become a public school teacher. Why be a teacher when you can be a doctor, attorney, engineer, or even (as I once hoped) an astronaut?

But I persisted. I spent the summer between my sophomore and junior year in college teaching middle school English language arts and U.S. government for a summer bridge program in DC. And I was good at it—I love kids, and the kids loved me. When I returned to campus that fall, I enrolled in teacher certification courses, and started student teaching in Durham High School. My senior year, I applied for and won a Rockefeller Brothers Fund Fellowship for Minorities Entering the Teaching Profession and led a tutoring program in a Durham County public elementary school. My work at the elementary school formed the basis for my senior honors thesis on the school’s challenges navigating North Carolina’s high-stakes accountability program. I realized then that my certification program was not going to prepare me. We were reading things like Plato, Rousseau’s Emile, or On Education, Descartes, and John Locke. I couldn’t imagine how those readings could prepare me to teach kids experiencing poverty in urban settings. What could Plato possibly know about Chicago Public Schools? Descartes and Locke espoused the idea that humans are blank slates until someone pours knowledge into their heads. I couldn’t reconcile that belief with my personal experience and worried that I would do my students a disservice without better training.

As a result, I decided to “cut bait” the spring of my senior year and began working in information technology, which wasn’t as much of a leap as it sounds. I started programming in Logo on my Commodore 64s and MS-DOS on PCs when I was in elementary school. I’d taken Advanced Placement Calculus in high school and took computer science classes in college to avoid taking more calculus to meet my math graduation requirements. While I loved calculus, my school used calculus courses to weed students out of the pre-med and engineering tracks. I didn’t have the patience for those games when I genuinely just wanted to learn and play with numbers. The millennium was fast approaching, and everyone was worried that the world would end because of the Y2K bug. Computer software historically programmed a year as two digits instead of four, and the concern was that software would confuse the year 200 for 1900 and short circuit financial, medical, utility, and other critical systems. IT companies and consulting firms feverishly plucked thousands of college students like me from our caps and gowns to help them stem the approaching disaster. When the clock struck midnight on January 1, 2000 without calamity, many claimed that the scare had been much ado about nothing. In reality, “nothing happened” because people like me sat in windowless offices for months fixing mainframe code, line by line, to ensure that our nuclear power plants wouldn’t implode. You’re welcome!

Not long after that, I saw that the writing was on the wall for the tech industry—the tech bubble was about to burst. I received an application in the mail for Harvard’s doctoral program in education because of my Rockefeller fellowship. Since I was living in Chicago at the time, I decided to apply to Northwestern as well. I got into both schools, but Northwestern offered me a full scholarship and Harvard didn’t, so the decision was simple. I first enrolled in Northwestern’s Human Development and Social Policy program to study education policy. As an undergrad, I found studying the influence of North Carolina’s accountability program and assessment policies on teaching and learning thrilling, but I changed course and eventually transferred to Northwestern’s Learning Science doctoral program. I missed working with kids and had started teaching middle school computer science part-time at a local school. I used my classroom as a laboratory and met faculty in the learning sciences program who were eager to guide me.

The learning sciences explore how people learn in and outside of formal learning settings. It’s an interdisciplinary field that draws from social and cultural psychology, cognitive science, computer science, and design. The program was full of people like me—current and former teachers and socially well-adjusted nerds who reflect inquisitively on the nature of education, consider what ails it, and dream up shinier and brighter ways to cure unproductive learning experiences. Becoming a learning scientist enabled me to combine my passion for teaching, programming, and education policy. It taught me how to design really cool things such as curricula, agent-based models, educational software and technology, and knowledge management systems. And it offered a concession to my relatives who urged me to reach beyond the classroom.

I chose federal contracting over an academic career for many of the same reasons I chose learning sciences—every project and client are different, allowing me to marry and flex my skills as needed. In addition, I knew I wanted to help people solve their problems and answer questions that were important to them, rather than those I or another academic might think were important. There is great value in answering those questions, but I’m motivated by helping clients simplify their worlds. Before joining Mathematica, I worked for one of our peer organizations and found that I really liked the world of federal contracting and doing research for philanthropies. I’ve done a lot of work on grant programs funded by the U.S. Department of Education and the National Science Foundation to increase STEM access and achievement for women and people of color, both in the K–12 system and in higher education. I’ve also done extensive work on school contexts—on how creating safe and healthy school environments, less exclusionary school discipline policies, and a more restorative juvenile justice system shape opportunities for students of color and students who are experiencing poverty. I’ve focused much of my career on addressing disparities in educational opportunity to help more students experience some of the opportunities my family sacrificed to give me.

However, the learning sciences isn’t a well-known field in the federal contracting space. For most of my career, I’ve leaned heavily on my methodological training as a researcher and a developer. I’ve had many opportunities to design interactive dashboards, simulations, decision support tools, and progress monitoring systems. I’ve had comparatively fewer opportunities to directly contribute my knowledge of cognitive development, expert-novice research, disciplinary literacy, and culturally responsive teaching until I joined Mathematica. The work I do here directly draws on my training in the learning sciences and the interdisciplinary nature of being a learning scientist. For example, on one of my projects, I direct the Equity Technical Assistance Center for the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). We use various learning modalities to design and deliver technical assistance to help HHS staff advance equity in their policymaking and program administration work. My training as a learning scientist is valued here and informs all that I do—it’s been exciting to be able to spend half of my time in technical assistance and the other half doing traditional research. At Mathematica, I can be me, fully realized.