I can’t separate my life experiences from who I am as a researcher. I don’t want to just do research that gets featured in jargon-filled journal articles that people won’t be able to understand or access because they’re locked behind a paywall. I want to do work that directly informs policy and leads to change, to conduct research that’s written in plain language and accessible to everyone. That’s why I was drawn to Mathematica. But to have the impact I want to have on the world, the impact Mathematica wants to have, equity needs to be intentionally infused throughout everything we do.

Equity-based work is about supporting and empowering others. This means bringing people from the communities we’re trying to support into our conversations and consulting with them about the methods we’re using, what they’re experiencing, and what they care about. We need to think critically about who’s impacted, who’s at the table, and how their life experiences have shaped their perspectives. To show that their feedback is shifting our thinking and informing the work, their voices should be embedded throughout the life of a research project, from design to the dissemination of findings. We also need to think critically about how we structure research teams and meetings so that they provide opportunities for diverse voices to be heard and for staff at all levels to showcase their skills.

My focus on equity and how I approach my work has been shaped by my experience belonging to multiple underrepresented groups. A first-generation Latina immigrant, I came to the United States when I was a year old. Like many immigrants from Latin America, my family left pretty much everything we had behind in our home country. My parents didn’t—and still don’t—speak much English. We started over in a predominantly Spanish-speaking community in urban New Jersey. When we relocated to rural Florida later in my life, I found myself enrolled in a Title I public high school with a graduation rate of only 60 percent. Many of my classmates faced challenges in completing high school, and the pathway to college was even more daunting. I was genuinely shocked when I received a full scholarship to attend Duke University.

But going from an underfunded, under-resourced high school in Florida to a university like Duke was a culture shock. I had an identity crisis when I realized there were so many people attending the university for whom this was the norm, who had generations of family members who had gone to college. I didn’t meet many other people from communities like mine, or many other first-generation immigrants. My background was such a significant part of my identity here that I began to ask, “Why me? How did I get here when so many others didn’t?” This piqued my interest in understanding factors that influence issues like college access. I wanted to understand what might have been different about my story compared to those of my peers and why there weren’t more people like us represented at institutions like Duke. As I became immersed in the world of research, I realized it’s not just high school experiences that influence post-secondary outcomes, but everything that happens much earlier on in life as well. Empowerment starts early.

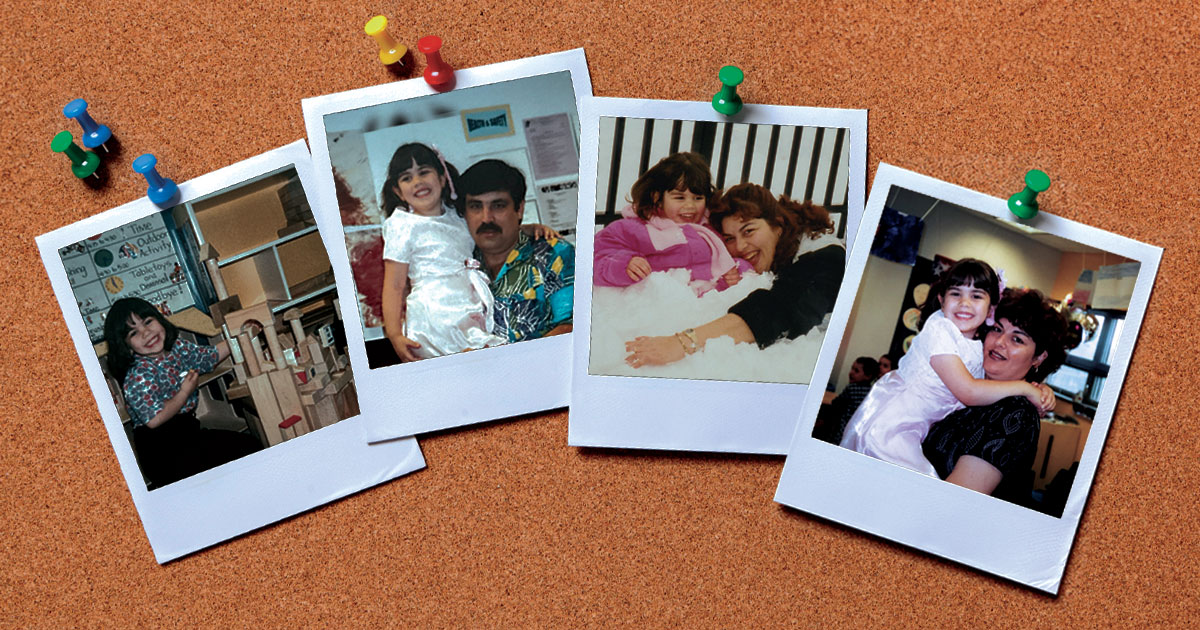

Though my family’s household income placed us below the federal poverty line, and we may not have had much in the way of material possessions, that's not what I remember most. I remember a warm, tight-knit household filled with love and support. As new immigrants, my parents quickly learned that they needed to be resourceful and connect with others who could help them navigate this country. Through connections with others in the community, they discovered a program called Head Start, designed to assist families with low incomes in preparing their young children for school. Thanks to this program, I received high-quality early care and education, setting a solid foundation from which to build on as I progressed through my schooling.

Growing up, my teachers didn’t make negative assumptions about me or my abilities because of the color of my skin, or my cultural background. My mom would also sit with me and help me study for school. This wasn’t easy for her, given that everything was written in English, but she persevered. She was always there, finding ways to help and encourage me. These themes of parental love, care, and togetherness surfaced in an early literacy study I worked on that focused on first-time parents from racially and ethnically diverse backgrounds. There are many strengths and insights that families from under-resourced backgrounds help bring into focus that we can, and should, elevate.

It’s important for those of us who were given opportunities and privileges, by whatever means, to help make way for others’ success. I want others to have access to the same kinds of supports that helped me succeed emotionally, mentally, academically, and professionally so they can experience upward mobility and live happy, fulfilling lives. I’m committed to being a lifelong learner, and part of the reason for that is because my parents taught me humility. I know I don’t have all the answers and can’t speak for everyone’s experiences. But improving public well-being starts with creating space for dialogue, listening to what the public wants and needs, and making these practices central to our research and recommendations. Communication needs to be a two-way street.

Jennifer is a recipient of the 2023 Patricia A. King Excellence in DEI Award. Named for longtime Mathematica board member Patricia (Pat) King, the award recognizes outstanding staff leadership and demonstrated commitment to advancing Mathematica’s vision for creating an equitable and just world and building an equitable and inclusive workplace.