Supporting the Fatherhood Journey: Findings from the Parents and Children Together Evaluation (PACT)

(OPRE Report #2019-50)

Where we come from, how we’re raised, the relationships we form, and the circumstances we encounter along the way—these experiences shape who we are as adults and as parents. For many fathers raised in poverty and facing various hardships, these life experiences create complex challenges and barriers to being a positive, active presence in their child’s life. An unstable life and lack of positive supports can undermine a father’s ability to actively bond with, care for, and raise his children.

Regardless of whether both parents live in the same home, children often benefit from having both in their lives. Research shows that children with engaged fathers experience fewer behavioral and emotional problems and have healthier relationships of their own.1 When a child's father is part of that child’s life, the path toward adulthood may provide greater stability and fewer obstacles.2,3

The Parents and Children Together (PACT) evaluation challenges the negative perception that limited-income fathers who live apart from their children are not interested in assuming the role and responsibilities of fatherhood. The Office of Family Assistance, part of the Administration for Children and Families (ACF) in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, funded the PACT evaluation, and ACF’s Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation oversaw a contract with Mathematica to conduct the evaluation. Read about these fathers’ lives and what some responsible fatherhood programs are doing to help these dads become better parents, providers, and partners and support them on this journey.

Martin's Story

For Martin, fatherhood began with a wake-up call.

Martin received an early-morning call that his daughter was about to be born. He quickly hung up the phone and ran nearly 45 blocks to the hospital. On watching his daughter’s birth, Martin said, “It was one of the greatest moments of my life.”

But underlying Martin’s excitement were harsh realities. Like many of the fathers we interviewed as part of the PACT evaluation, Martin experienced many interconnected life challenges that posed a risk to his ability to be there for his daughter—as both a father and a financial provider. The desire to address these challenges and become a better father motivated Martin, and other men like him, to voluntarily enroll in a responsible fatherhood program. These programs provide services in three key areas: parenting education, employment and economic stability, and healthy marriage and relationship skills.

Martin

“It was one of the greatest moments of my life.”

The PACT Evaluation

Research shows that fathers matter in their children’s lives. Greater contact with nonresidential fathers has been associated with fewer child and adolescent behavior problems.1 But fathers need to be more than just present. The quality of father–child interactions also matters.2,3 Nonresidential fathers’ engagement in child-related activities has been linked to positive social, emotional, and behavioral adjustment in children.

To support responsible fatherhood and promote child well-being, Congress has funded the Responsible Fatherhood grant program since 2006. The Office of Family Assistance (OFA), part of the Administration for Children and Families (ACF) in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, administers the grant program.

To learn more about the effectiveness of these programs, OFA funded, and ACF’s Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation oversaw, a contract with Mathematica Policy Research to conduct the Parents and Children Together (PACT) evaluation (see PACT Responsible Fatherhood Evaluation Characteristics). More than 5,500 fathers participated in the PACT evaluation by enrolling at four responsible fatherhood programs, with more than 2,500 fathers being offered program services. The PACT evaluation had three goals:

- Understand how responsible fatherhood programs are designed and implemented

- Describe the lives of fathers who enroll in these programs

- Contribute to the evidence base of what works to increase positive father involvement in children's lives

This online report gives a snapshot of the fathers and the programs that serve them. Click each chapter to learn more.

PACT Responsible Fatherhood Evaluation Characteristics

- Four fatherhood programs participated in the evaluation

- Sample size: 5,522 fathers enrolled from 2012-2015

- 50% randomly assigned to receive program

Process Study

Examines how RF programs were structured and operated as well as fathers’ participation in the services offered.

- This included in-depth site visits with the four programs

- Staff participated in in-depth interviews regarding their experiences delivering the program

- Focus groups were also conducted with participants at each site asking about their program experiences

- Analyzed data from a management information system collecting program data (that is workshop attendance, service contacts, and referrals)

Qualitative Study

Focuses on understanding the broader contexts of fathers’ lives through three rounds of in-depth interviews with a subset of fathers assigned to the program group.

- Involved 87 of the 2,761 fathers receiving the RF program

- Three rounds of in-depth interviews approximately one year apart from each other

- Topics of discussion included experiences during childhood, relationship history, parenting, relationship with their children, employment, and experiences with the court system.

Impact Study

Examines the effects and changes that program participation had on the fathers who received the program compared with those who did not.

- All enrolled participants received baseline survey

- Randomly assigned to receive program services

- Follow-up survey given one year post-enrollment

Summary of Findings

PROCESS STUDY FINDINGS

- Across all program services areas, fathers received 45 hours of content, on average, ranging from 15-88 hours depending on the program

- Programs worked to support fathers’ personal development in addition to offering parenting, relationship, and employment services

- For more information, read the process study report on the RF programs.

QUALITATIVE STUDY FINDINGS

- Fathers faced many adversities in childhood and as adults, but fatherhood motivated many to turn around their lives

- Fathers struggled with co-parenting relationships, child support, and having access to their children

- Past and ongoing economic instability, often linked with a history of incarceration and a criminal record, were significant barriers to fathers’ ability to support themselves and their children.

- For more information, read the qualitative study report.

IMPACT STUDY FINDINGS

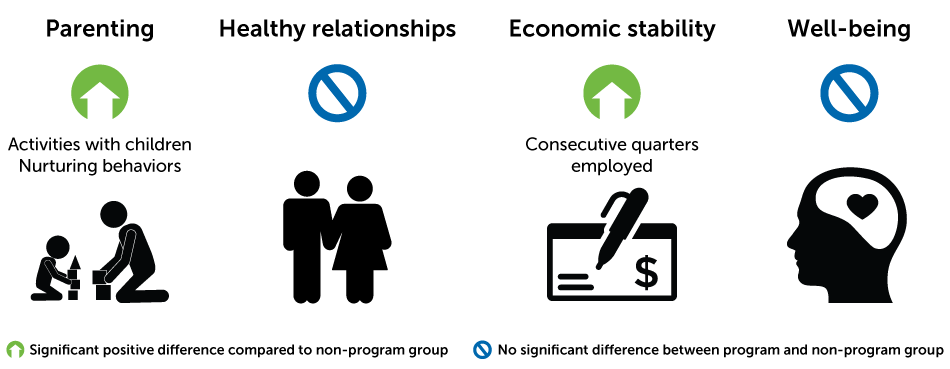

- The responsible fatherhood programs in PACT showed some success in improving fathers’ parenting behaviors and employment stability.

- The programs did not improve fathers’ earnings and coparenting or romantic relationships.

- For more information, read the impact study report on the RF programs.

The Responsible Fatherhood Programs in PACT

Connections to Success

- Location: Kansas City, Kansas, and Kansas City, Missouri

- Organization history: 10 years of providing personal development and employment services to prison re-entry populations

- Mission statement: “We inspire families to realize their dreams and achieve economic independence by providing hope, resources, and a plan.”

- Program name: Successful STEPS

- Target population: Limited-income fathers who are interested in getting a job or improving their employment situation

- Program description: Group based daily workshop lasting two and a half weeks, and an open-entry workshop for graduates of the two-week program

- Partners: Domestic violence organization and Kansas and Missouri child support agencies

Fathers’ Support Center

- Location: St. Louis, Missouri

- Organization history: Served limited-income fathers for more than 17 years, with the goal of helping them become self-sufficient, responsible, and committed to strong family relationships

- Mission statement: “Our mission is to foster healthy relationships by strengthening families and communities.”

- Program name: Family Formation Program

- Target population: Limited-income fathers who are interested in getting a job or improving their employment situation

- Program description: Cohort-based daily workshop lasting six weeks

- Partners: Domestic violence organization, Missouri child support agency, and two local employment agencies

Goodwill-Easter Seals Minnesota

- Location: Minneapolis and St. Paul, Minnesota

- Organization history: Provided employment and parenting services for more than 15 years to fathers who were unemployed or having trouble paying child support

- Mission statement: “Our mission is to eliminate barriers to work & independence.”

- Program name: The FATHER Project

- Target population: Limited-income fathers ages 17 to 40

- Program description: Weekly parenting and healthy relationship workshops; single-day employment workshop

- Partners: County child support agencies, domestic violence agency, community legal services, adult basic education provider, and an early childhood education and home visiting program

Urban Ventures

- Location: Minneapolis, Minnesota

- Organization history: Two decades of providing parenting services to limited-income fathers, with a focus on African American men

- Mission statement: “Educating children, strengthening their families, and building a healthy community.”

- Program name: Center for Fathering

- Target population: Limited-income fathers over age 18

- Program description: Separate weekly workshops on parenting, relationships, and job readiness

- Partners: Street outreach community-based organization, domestic violence agency, and county child support agency

Learn about these programs from the leaders at each organization

Personal Development

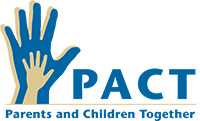

The typical father in the PACT evaluation was an African American man in his mid-thirties with low levels of education and income. Fathers came to the program with complex challenges. Their childhoods were typically spent in high-stress home and neighborhood environments, and many experienced traumatic events. Participants’ fathers were often absent from their own lives, leaving them to navigate fatherhood without the benefit of a positive role model. Almost all had been involved with the court system, and many had been incarcerated. As adults, they continued to experience adversity in the form of job, income, and housing instability; racial discrimination; and mental health issues like depression and anxiety.

Many fathers said they were ready to change—both for the sake of their children and for moving their own path forward. Most accepted responsibility for their past behavior and expressed that fatherhood motivated them to transform their lives. These men wanted to do something positive for themselves and their children, and to be the father they never had.

Personal development services

An important component of the programs in PACT was to help fathers address personal challenges that often created barriers to being effective parents, providers, and partners. To help fathers develop foundational skills, habits, and attitudes, the programs covered topics such as what it means to be a man, being accountable and responsible, problem-solving and decision-making skills, defining values, and setting goals. Group workshops encouraged fathers to share experiences and receive support from other fathers. Fathers reported that they valued peer support in group settings. They easily connected to facilitators and staff who were program graduates or had similar backgrounds.

One-on-one meetings with their program case manager provided fathers additional opportunities to focus on their personal development and address barriers to achieving greater economic stability and becoming more involved and effective parents. Across all programs, fathers received an average of eight hours of content related to personal development. Across programs, between 51 and 63 percent of fathers engaged in at least one workshop session that covered personal development.

Note: N = 5,522. Sites began enrolling fathers from December 9, 2012, to February 13, 2013. Sample includes all fathers who were randomly assigned.

Preston

“It gave me a different outlook on life.”

Program staff discuss personal development services

Parenting and Co-Parenting

PACT FACTS: A Snapshot of Enrolled Fathers and Their Children

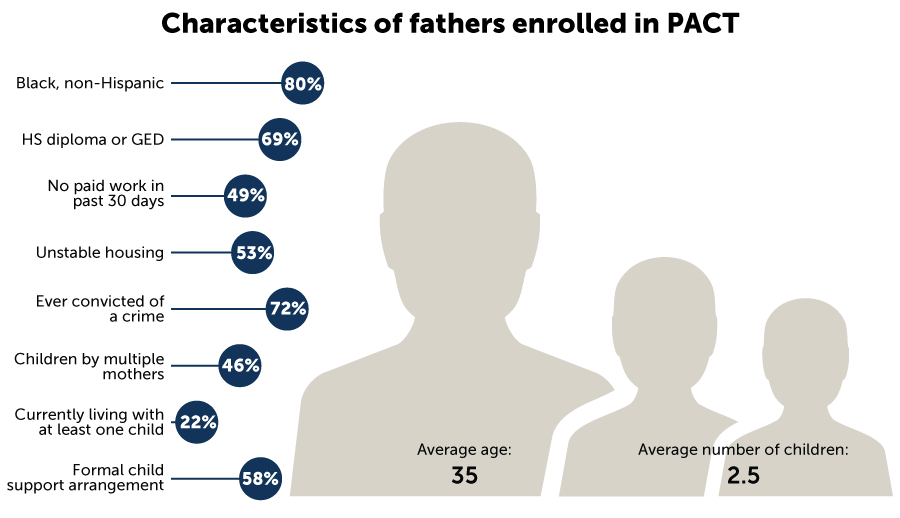

- Fathers enrolled in PACT had, on average, two to three children.

- Fathers often had children with multiple mothers; most fathers had some form of contact with all their children at time of enrollment. Nine in 10 fathers had some recent contact with at least one child.

- About 60 percent of fathers reported spending time weekly with at least one child; some saw their children more often.

- Eighteen percent of fathers stayed overnight with all their children regularly, including 11 percent who lived with all their children.

Note: N = 5,522. Sites began enrolling fathers from December 9, 2012, to February 13, 2013. Sample includes all fathers who were randomly assigned.

Despite a lack of shared custody, parenting time agreements, and strong co-parenting relationships, fathers longed to become more involved parents. In fact, they reported that their desire for more involvement and to become better fathers were the main reasons for enrolling in these programs. “Being there” for their children was incredibly important to these fathers, especially for those whose own fathers were mostly absent when they were growing up. “Being there” meant spending more time with their children—being physically and emotionally there for them—even if they could not financially support their children. The father role became a powerful reason to turn their lives around and encourage their children to take a better path different from what they had chosen.

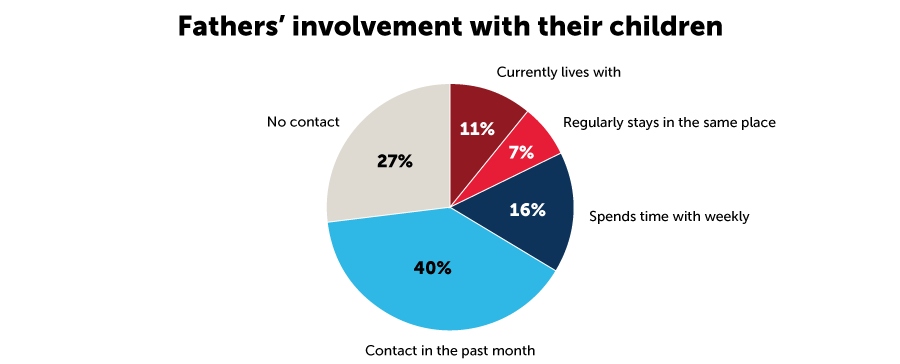

During in-depth interviews with a subset of fathers who enrolled in responsible fatherhood programs, some described cooperative co-parenting relationships, but most described disengaged or conflicted relationships with some or all of the mothers of their children. Co-parenting relationships were either marked by poor communication and verbal disagreements with their children’s mothers or they were fragile, disengaged relationships, with little to no communication or co-parenting occurring between the parents.4

Most fathers in conflicted co-parenting relationships struggled to establish or maintain contact with their children and were extremely frustrated over their lack of access. This lack of access to their children was, in turn, the most common source of conflict between the fathers and the mothers of their children, continuing a cycle of co-parenting conflict and lost opportunity for greater father involvement. Some fathers expressed needing help with fixing their relationship with the mothers of their children in order to become better parents.

Parenting and co-parenting support services

Programs offered group-based, multi-session workshops on parenting skills. Each program used a different structured curriculum for its parenting workshop, but typically included content on child development, the meaning and responsibilities of fatherhood, and co-parenting. Workshop curricula included a range of other topics, although the mix of topics varied by program. These included parenting skills such as disciplinary strategies, handling challenges to effective parenting (such as stress or unexpected life events), and meeting child support obligations and navigating the child support system. For fathers to effectively apply parenting and co-parenting skills, they would benefit from assistance with parenting time agreements, visitation rights, and custody, which was not available through the responsible fatherhood programs.

Fathers need services to help navigate and potentially improve their conflicted and disengaged co-parenting relationships with the mothers of their children. To improve co-parenting skills, programs included instruction on relationship skills such as non-confrontational communication. Fathers also received some parenting or co-parenting content through individual meetings with program staff. Parenting support varied by program, but on average, fathers received services through workshops and one-on-one interactions with program staff. Averaged across programs, fathers received about nine hours of parenting-focused content.

Raashad

“It’s a fight to try to be a part of her life.”

Martin

“It’s just about spending time with them.”

Program staff discuss parenting services

Romantic Relationships and Marriage

Many fathers were in their teens or early 20s when they had their first child. More often than not, they came to the responsible fatherhood programs with a history of troubled romantic relationships, including past infidelity or intimate partner violence (from one or both partners). Fathers often attributed the high level of conflict in their romantic relationships to a mix of immaturity and the financial and emotional stresses related to raising an infant. Most of these relationships eventually ended, and, for some, the conflict continued as they attempted to co-parent despite not being romantically involved.

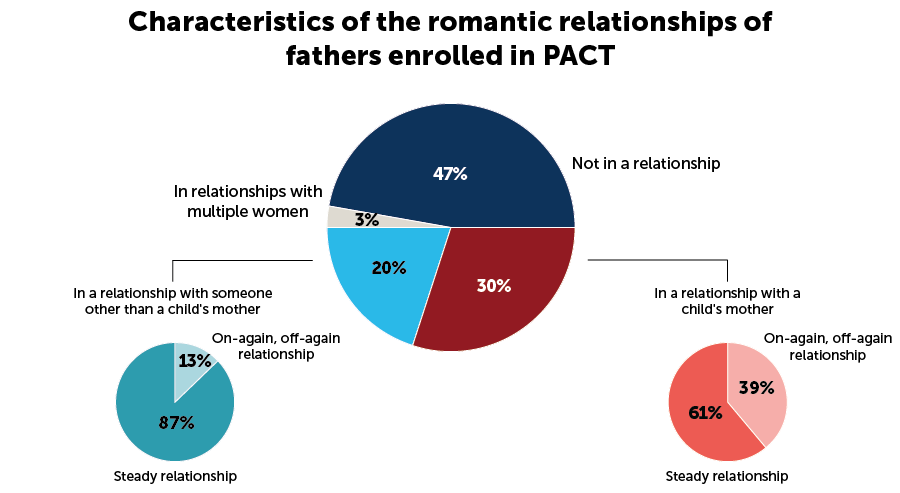

About half of the fathers who enrolled in PACT were in a romantic relationship at enrollment. This includes about 30 percent who were still involved with the mother of at least one of their children and about 20 percent who were involved with a woman with whom they did not share a child. On-again, off-again relationships were more prevalent among fathers in a relationship with one of their children’s mothers. Although relatively few fathers—9 percent—were married to anyone at the time of enrollment, nearly one-third reported having been married at some point, usually to a mother of their children.

Healthy relationship services

Programs offered group-based workshops to learn healthy marriage and relationship skills. Although the content and structure of these workshops varied by program, the group-based approach allowed fathers to receive encouragement from other fathers grappling with similar relationship issues. Topics commonly focused on conflict management and communication skills, and the characteristics of healthy and unhealthy relationships including intimate partner violence, gender roles, relationship expectations, and building trust and intimacy. Within nine months of enrollment, 27 to 59 percent of fathers attended at least one workshop session addressing healthy marriage and relationships. Across the four programs, fathers received about six hours of healthy relationship content, on average.

Note: N = 5,522. Sites began enrolling fathers from December 9, 2012, to February 13, 2013. Sample includes all fathers who were randomly assigned.

Program staff discuss healthy relationship services

Economic Stability

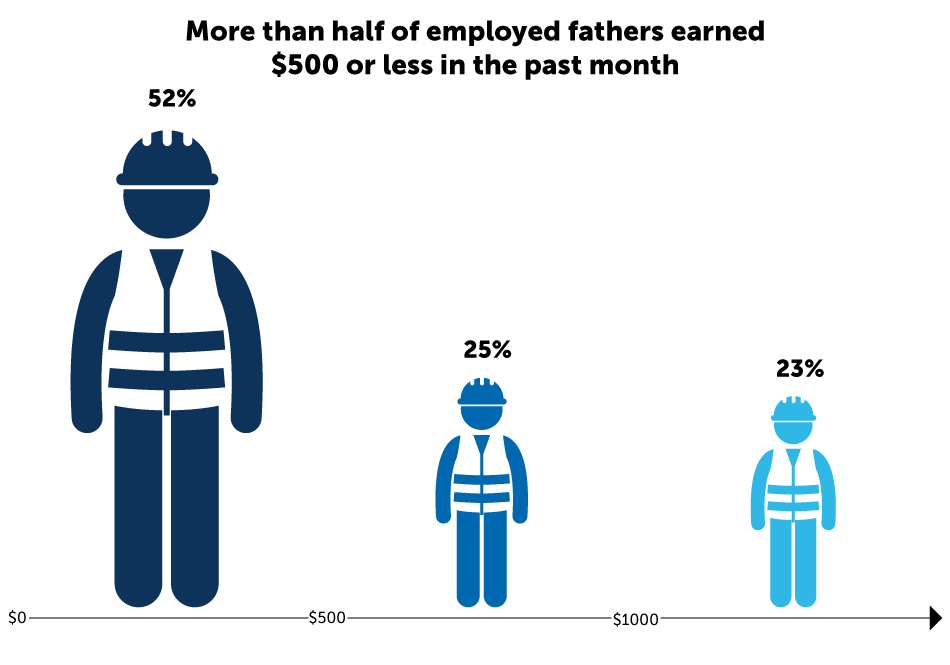

Most fathers experienced high levels of unemployment. When they found work, it was typically in low-paying, unstable jobs. Their precarious financial situation made it difficult to provide for themselves and their children. Half of fathers were unemployed in the month before enrollment. Among those who were employed in the month before enrollment, earnings were low.

Employed fathers who participated in in-depth interviews usually described low-paying jobs that were temporary or lacked consistent hours. Most commonly, they worked in food service, construction, maintenance, landscaping, or warehouse work. Though they generally felt that some work was better than none, these men couldn’t count on a steady paycheck. This made it difficult to know whether they’d be able to pay their child support or cover their own necessities like food and rent. More than one-third of the fathers interviewed said they relied sporadically on odd jobs to make ends meet.

Most men also faced several barriers to employment. Fathers often had criminal records and many lacked the educational requirements, employment histories, and skills needed to obtain gainful employment. These fathers also typically lacked social networks or connections that could help them find employment.

Employment services

The responsible fatherhood programs offered group- and individual-level employment-focused activities to help fathers improve their ability to work and find a job. Group-based activities were most often focused on job-readiness skills, such as interviewing techniques, resume development, and job searching. Employment case managers helped individual fathers get into job training or certification programs. One program arranged for fathers to engage in self-directed activities each afternoon over many weeks to build their work readiness, such as computer literacy classes or unpaid on-the-job community service. On average, fathers received about 20 hours of employment content. The average number of hours of employment content varied widely across programs, ranging from 2 to 47 hours.

Note: N = 5,522. Sites began enrolling fathers from December 9, 2012, to February 13, 2013. Sample includes all fathers who were randomly assigned.

Fathers and program staff discuss fathers’ economic stability

Program staff describe how they address employment barriers

Providing Child Support

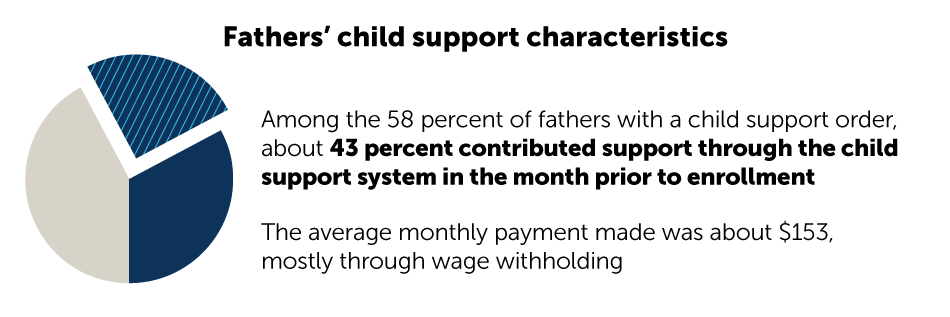

Fathers were frustrated in their struggle to financially support their children. Because so many fathers entered the programs with low levels of education, earnings, and job stability, their ability to support themselves and their children was limited.

More than half of the fathers had formal child support orders. Fathers struggled to pay child support and often owed back support (also known as arrears) due to periods of unemployment or incarceration. They had challenging experiences with the child support system and feared harsh consequences for failure to pay. In addition, about one-third of all fathers provided “informal” support that included giving cash directly to mothers of their children and providing non-cash support, such as food, clothes, school supplies, or toys for their children. Almost one-quarter of fathers were living with at least one child and may have contributed economic support by serving as the primary breadwinner or financially contributing to the household.

Program services related to child support

Fatherhood programs often partnered with their local child support agencies. Through these partnerships, programs provided the following:

- Informational sessions on child support policies and processes

- Materials to help fathers understand their child support rights and responsibilities and develop parenting time agreements

- Increased access to child support staff and services by co-locating child support and fatherhood staff

- Reduction of state-owed arrears based on program participation

- Assistance with reinstating driver’s licenses that had been revoked due to non-payment of child support

Note: N = 5,522. Sites began enrolling fathers from December 9, 2012, to February 13, 2013. Sample includes all fathers who were randomly assigned.

Fathers talk about financially supporting their children

Child support staff describe helping fathers with driver’s license reinstatement

Fathers’ Responses to Services

Fathers describe their program experiences

Common Themes Based on In-Depth Interviews and Focus Groups with Fathers

Fathers bonded with men in the groups and the program staff. They felt a sense of brotherhood with men in the program and viewed staff as role models. These bonds helped them stick with the program and kept them motivated to improve themselves.

Fathers were drawn to and valued the personal development content. They credited the program for helping them reflect upon the course of their life, encouraging them to take greater responsibility for their actions and feelings, and providing a safe opportunity to express their emotions. Fathers appreciated learning skills and information that motivated them to become better men and fathers.

Fathers believed the programs helped them become better parents. Fathers said that program attendance empowered them to become more engaged and nurturing parents. They also felt the program helped them become more than traditional disciplinarians and form deeper emotional connections with their children. Fathers found content on how to communicate with their children helpful in learning how to better relate to them and rebuild relationships. They embraced the idea that they could offer their children emotional support and connection, even if they could not provide much in the way of financial support.

Fathers reported gaining valuable relationship skills that improved communication and co-parenting. Fathers discussed how these skills helped them improve their conversations around money with their current romantic partners or former partners with whom they had children. Some experienced more cooperative co-parenting as a result of their improved communication and conflict management skills. Having learned about the characteristics of healthy relationships, fathers also came to realize how some behaviors, such as being emotionally manipulative and self-centered, may have sabotaged their relationships.

Fathers expressed the need for free or reduced-priced legal representation. The responsible fatherhood grant did not allow grantees to use these funds to provide legal representation for fathers. If provided, such services required other sources of funding. Two programs in PACT offered limited legal services to assist fathers with establishing paternity, child support, custody, and visitation concerns. Several fathers discussed the role the programs played in helping them secure visitation with their children. However, some fathers wanted more help, including legal assistance, with securing visitation, shared custody, or parenting time.

Fathers wanted greater access to their children and desired help resolving what they perceived to be an unfair disconnect between paying child support and access to their children. Fathers felt they deserved access to their children if they were paying child support. Fathers found the basic information provided about child support useful, such as the how their child support order amount was calculated, their rights to challenge an order, and their responsibility to pay even if they did not have access to their children. Some felt that this led to improvements in their situation. Still, many fathers felt that their child support orders were not in line with their income and increased their financial difficulties. They wanted more assistance in modifying child support orders or addressing arrears.

Fathers gained job-seeking skills through the program services but still struggled to achieve greater economic stability. Fathers at each program reported that they learned specific job-seeking skills, including how to develop a resume, complete an online job application, and answer sensitive questions in a job interview, particularly questions about past felony convictions and jail time. Still, fathers experienced their criminal background as a major roadblock to attaining living-wage jobs and would have liked more help with job placement.

Key Impact Study Findings

The responsible fatherhood programs had some success in improving fathers’ involvement in their children’s lives. The programs improved fathers’ self-reported nurturing behavior and engagement in age-appropriate activities with children. Nurturing behaviors included showing patience when the child was upset or encouraging the child to talk about his or her feelings. Depending on the age of the child, age-appropriate activities included reading books or telling stories to the child, feeding the child or having a meal together, playing with the child, or working on homework together. However, the programs did not affect the amount of in-person contact fathers had with their children or the financial support they gave them.

The programs did not affect the quality of fathers’ relationships with the mothers of their children. Fathers in the program and non-program groups reported similar levels of agreement about their ability to form a good coparenting team with the mothers of their children. The programs also did not affect the proportion of fathers who were married to or in a steady romantic relationship with any mother of their children.

The responsible fatherhood programs led to a modest increase in employment stability. The effect on employment stability, however, did not translate to improvements in earnings in the year after fathers enrolled in the programs.

The programs did not affect fathers’ well-being. Fathers in the program and non-program group did not differ on how frequently they experienced depressive symptoms or their belief in whether they are in control of their own life circumstances.

Additional PACT Resources

The PACT evaluation has produced a variety of reports. For more information and a complete listing of all available reports, please visit the OPRE website. To contact the PACT evaluation team, please email info@mathematica-mpr.com or contact the PACT project director, Sarah Avellar, at savellar@mathematica-mpr.com.

References

1 Sobolewski, J. M., and King, V. “The Importance of the Coparental Relationship for Nonresident Fathers’ Ties to Children.” Journal of Marriage and Family, vol. 67, 2005, pp. 1196–1212.

2 Stewart, Susan D. “Nonresident Parenting and Adolescent Adjustment: The Quality of Nonresident Father-Child Interaction.” Journal of Family Issues, vol. 24, no. 2, 2003, pp. 217–233.

3 Marsiglio, W., P. Amato, R. Day, and M. Lamb. “Scholarship on Fatherhood in the 1990s and Beyond.” Journal of Marriage and the Family, vol. 62, 2000, pp. 1173–1191.

4 It is important to remember that we are reporting this from the perspective of the fathers and not the mothers. Although recognizing that every story has at least two sides, this research focuses on the father’s perspective.

5 Friend, Daniel J., Jeffrey Max, Pamela Holcomb, Kathryn Edin, and Robin Dion. “Fathers’ Views of Co-Parenting Relationships: Findings from the PACT Evaluation.” OPRE Report No. 2016-60. Washington, DC: Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2016.

Acknowledgments

Development of this report was a collaborative effort. At Mathematica, the following people contributed:

Mathematica researchers: Pam Holcomb, Heather Zaveri, Daniel Friend, Robin Dion (retired), Scott Baumgartner, Liz Clary, Angela Valdovinos D’Angelo, Sarah Avellar, Diane Paulsell

Mathematica communications staff: Gary Axelrod, Rich Clement, Brigitte Tran, Robert Williams, Carmen Ferro

Mathematica Web developer: Scott Freeman

We wish to thank the Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation (OPRE) and the Office of Family Assistance (OFA) at the Administration for Children and Families (ACF) for its support of the Parents and Children Together (PACT) evaluation. We are deeply grateful for the excellent guidance and feedback provided by our OPRE project officer Seth Chamberlain and project monitor Kathleen McCoy. This report also benefitted from insightful comments by ACF leadership: Naomi Goldstein, Maria Woolverton, Charisse Johnson, and Robin McDonald.

We also wish to thank the grantees and their staff, who hosted us for site visits and participated in interviews. In particular, we would like to thank the leadership at each program: Halbert Sullivan and Cheri Tillis (Family Formation Program); Andrew Freeberg and Guy Bowling (FATHER Project); Brad Lambert, Kathy Lambert, and Brandi Jahnke (Successful STEPS); and John Turnipseed and Stan Hill (Center for Fathering).

Finally, and most importantly, we wish to thank the men who responded to the baseline survey and participated in in-depth interviews for openly sharing their views and experiences, and providing us with such a rich and nuanced portrait of their life circumstances and challenges.

Suggested citation:

Holcomb, Pamela, Heather Zaveri, Dan Friend, Robin Dion, Scott Baumgartner, Liz Clary, Angela Valdovinos D’Angelo, and Sarah Avellar. “Supporting the Fatherhood Journey: Findings from the Parents and Children Together Evaluation (PACT).” OPRE Report #2019-50. Washington, DC: Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2019.