A journalist recently asked a colleague and me about the “noncognitive skills revolution,” or policymakers’ surging interest in abilities like self-control and “grit.” As someone who spent much of graduate school studying noncognitive skills, I had a mixed reaction. On the one hand, it was reassuring to see the media and policymakers take seriously a broader set of skills than those captured by test scores. On the other hand, “revolution” is a misnomer. As noted in a recent paper, educators like Horace Mann have been stressing the importance of skills like persistence and motivation for centuries—and even the creators of the modern IQ and achievement tests warned of these tests’ limitations.

In the age of accountability, common sense is not enough to convince policymakers of the limitations of test scores and importance of noncognitive skills—these decision makers require hard evidence. Over the past 30 years, social scientists have provided this evidence, establishing the following facts:

- Test scores miss a lot—they explain at most 15 percent of what makes people successful in terms of outcomes like earnings and employment.

- Noncognitive skills can be measured, and these measures predict meaningful life outcomes above and beyond test scores.

- Schools and interventions can improve life outcomes without improving test scores.

- Noncognitive skills are malleable and can be enhanced through interventions. If there has been a “noncognitive skills revolution,” it has been grounded in measurement and data collection.

This kind of evidence has caused policymakers to shift away from relying exclusively on achievement test scores to measure school performance. Guided by the recent Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA), states are scrambling to incorporate nonacademic skills into school measurement systems, raising the question: “What measures should schools use and for which purpose?” The challenge is that hard evidence on soft skills comes primarily from low-stakes research studies, and little is known about how commonly used measures will hold up if schools use them to guide policy.

Going forward, one possibility is to use self-reports, the measures most frequently used in research studies. A group of school districts in California has incorporated self-reported measures of socio-emotional (noncognitive) skills into their metric for school performance. As with the creators of achievement tests a half-century ago, developers of noncognitive skill measures like Angela Duckworth have warned about the limitations of using self-reports in this way. For example, consider the following question used to measure “conscientiousness”—the tendency to be organized and complete tasks.

Please indicate the extent to which you agree or disagree with the statement: “I am someone who tends to be lazy.” (1 = Disagree strongly, 2 = Disagree a little, 3 = Neither agree nor disagree, 4 = Agree a little, 5 = Agree strongly)

If measures like this one were used in a high-stakes setting—for example, with school funding tied to responses to these questions—it seems likely that teachers could convince even the least motivated students to write “1” more frequently. If the results were publicly reported (or any consequences attached), principals might feel pressure to encourage students to answer favorably to improve the appearance of their school.

Even if principals and teachers encouraged students to report accurately, other forms of bias might render these measures incomparable across schools. In particular, these measures can suffer from reference bias—the possibility that students rate themselves relative to their peers rather than to the whole population. For example, a student at a competitive magnet school might view himself or herself as lazier relative to peers, but if the same student attended a different school where peers spent fewer hours doing homework, the rating could be different. Similar issues could arise if these measures were used within schools to identify students who might need more assistance.

Using school administrative data to measure noncognitive skills is a promising alternative to self-reports. School districts already collect a variety of measures on absences, grades, credits earned, and disciplinary infractions. These types of measures have been shown to correlate with traditional measures of noncognitive skills—earning good grades requires showing up to class, completing assignments on time, and behaving well.

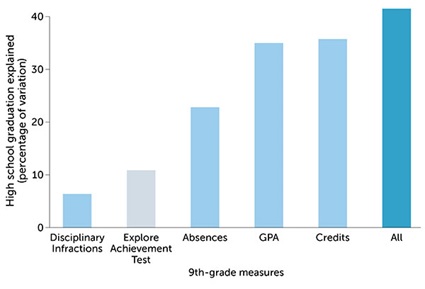

More important, these other administrative data are highly predictive of meaningful outcomes. The figure [source: Chicago Public School administrative records as analyzed in Kautz and Zanoni (2016)]. shows the extent to which ninth-grade measures of achievement tests, grades, absences, credits earned, and disciplinary infractions predict high school graduation among a cohort of students in the Chicago Public Schools. The achievement test score predicts only about 10 percent of the variance. Absences, grades, and credits earned predict two to three times as much of the variance. All of the measures combined explain about 40% of the variance, leaving most of the variance unexplained. As with self-reports, not all of these measures would be appropriate for high-stakes accountability. On the other hand, if the goal is to identify students who likely need additional assistance, these measures provide more information than achievement tests. The Chicago Public Schools are already using the “on-track indicator” (a measure based on credits earned) as a way to track students who might need additional assistance.

Although there have been clear advances in measures of noncognitive skills, the enthusiasm for them has outpaced the research. Standard measures might suffer from bias even if used as a diagnostic tool and are prone to faking if used for accountability. A stepping stone is to further explore the use of administrative data that schools already collect. Along with colleagues, I am working on a study of the Chicago Public Schools funded by the Spencer Foundation to investigate reference bias, the role that incentives can play in self-reports, and the extent to which administrative data capture noncognitive skills. Stay tuned for results to come.