Late last week, Congress passed the largest economic stimulus package in our nation’s history, one of several ways Congress is helping America weather the economic downturn caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. The $2 trillion package includes a substantial nationwide increase in unemployment insurance (UI) compensation (amounting to a $600-per-week benefit increase). This $260 billion infusion of funds for UI is a huge step forward in helping workers who’ve lost jobs as a result of COVID-19. The legislation also created the Pandemic Unemployment Assistance program to support individuals who are not typically eligible for UI benefits, such as self-employed and contract workers. These changes help states respond to the specific needs of this crisis, but they also carry an additional administrative burden to support proper implementation. Even in calmer times, adding complex changes can be hard for state agencies that have faced flat or declining funding and staffing levels, and now is anything but calmer times.

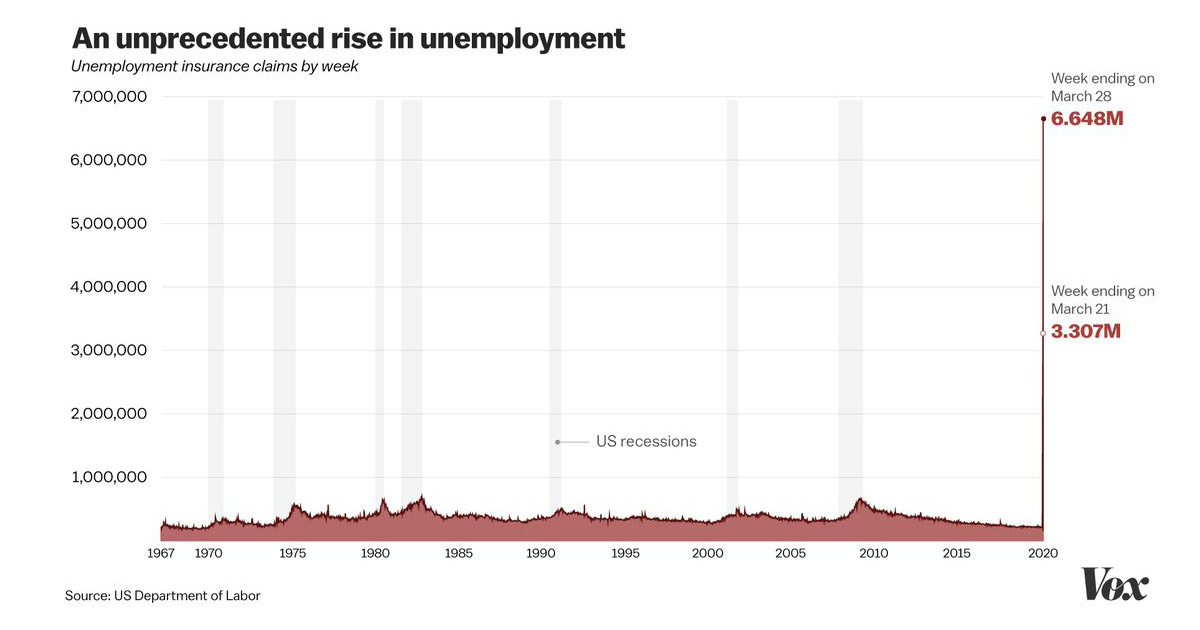

The data coming out of the U.S. Department of Labor are starting to tell a startling story. Recently released data showed nearly 10 million people filed initial unemployment claims in the last two weeks, including over 6.6 million people last week alone. That easily surpasses all previous records for initial unemployment filings (shown in the chart produced by Vox News below). And today, another round of data confirmed what many people expected was coming, the end to the longest stretch of job creation in American history, as the U.S. economy shed 701,000 jobs in March.

Through this economic stimulus package, the federal government is providing states with billions of dollars to help cover unanticipated costs. It’s no surprise, however, that policymakers and state program administrators are facing unprecedented administrative burdens as more and more people submit claims. Helping states manage this challenge, ease administrative burdens, and ensure payments reach those who are most in need is no easy task.

Although the full extent of COVID-19’s impact on the economy remains to be seen, we can learn lessons from the Great Recession of the late 2000s to help inform decision making and reduce the potentially devastating consequences that will be felt years from now. Drawing on lessons learned from this project for DOL, here’s what we know:

- To ensure that this infusion of funds reaches those who need it most and has the greatest chance of helping the economy recover as quickly as possible, get creative about who provides services and how services are managed. Before the Great Recession, many states were understaffed and faced government-wide hiring freezes. UI programs in these states had to seek waivers or exemptions from statewide actions, contributing to lags between when the staffing need was perceived and when new staff could begin processing claims. Although the economy before the start of the COVID-19 pandemic was much stronger than it was in the late 2000s when those hiring freezes were implemented, states today will face similar challenges as a result of COVID-19, particularly given the difficulty of predicting the severity of the problem and how many additional staff will be necessary. States might want to try the following approaches:

- Use an all-hands-on-deck approach to deepen the pool of workers who can process claims. States will likely need to tap into all available UI staff and hire new staff. Colorado, for example, has shifted about 90 staff from their regular duties to support their call-center staff. In addition to bringing in staff from other business units in UI and cross-training as necessary, states might be able to tap into retired and intermittent workers who are already trained. Washington State, for example, has hired more than 100 staff members to help administer their unprecedented number of unemployment claims. In the next month, they could hire as many as 1,000 more. States also will want to consider upgrading phone lines and information technology (IT) capacity to handle the bigger volume of claims.

- Increase training capacity by simplifying or condensing the training process, and automate where possible. To mitigate training constraints, states can create a shortened training series for new hires and can conduct their UI trainings online.

- Provide virtual training to community leaders or staff at community hubs, so that they can be ready to help unemployed workers as soon as possible. Although many community hubs are currently closed, many unemployed workers will likely struggle to find work even after the shelter-in-place and lockdown orders are over and will need continued assistance navigating the UI system. Training non-UI staff who work at community hubs to answer basic questions about UI eligibility or about the UI program can help unemployed individuals navigate the UI system and relieve strain on UI call centers.

- Use metrics to continuously monitor and improve operations. Tracking daily progress on claims and producing electronic reports on timeliness can be used to improve operations and develop and compare performance measure benchmarks.

- Adjust and modernize data technology systems to work for different types of claims. States rely on their IT systems to process regular UI claims and produce reports; however, during times of emergency such as this, states face challenges in making timely adjustments to their IT systems to serve all claimants. For example, few UI systems easily allow for the differences in benefit amounts, durations, and eligibility requirements that arise because of new federal legislation. States are likely to face even greater challenges now, given the expansion in coverage to traditionally ineligible workers. Here’s what helped many states to manage this challenge during the Great Recession:

- Consider alternatives to the traditional call-center structure, including using cell phones and email forms for inquiries and telecommuting (if not already doing so). States might choose to implement new call-center technology such as virtual hold, which allows a caller to choose between remaining on the phone in a waiting queue or being automatically called back by a computer system when an appropriate staff person becomes available. Some states have also set up a so-called gating system for those filing claims online to slow down web traffic, allowing only people with certain last names to log on and apply for benefits at different times.

- Make claims materials more user-friendly so people can serve themselves. Changing website automation, automated phone systems, and external-facing documentation or notices to be more user-friendly makes it easier for potential claimants to serve themselves.

- Plan how to best use federal resources by quickly distributing funds for scale-up. States will have to quickly develop plans to use federal resources for UI and other programs focused on pandemic-related assistance. It’ll be essential for states to review and implement new rules, guidance, and regulations that will affect their ability to distribute funds. Two particularly helpful resources from DOL, this March 12 letter and this March 22 letter, to all state workforce agencies provide guidance to states regarding UI eligibility for individuals affected by COVID-19 and offer information about additional funding and flexibilities given to states in light of the crisis. Based on our past research, here’s what helped many states quickly implement changes during the Great Recession:

- Coordinate with state partners to share resources, including optimizing IT resources and assignments for cross-trained staff. Consider establishing lines of communication between various agencies to help scale up operations, like a shared phone system and cross-agency meetings to decide how to optimize phone capacity.

- Identify and share targeted updates with staff to help reduce duplication of work, especially for staff who receive questions from claimants. Having easily accessible information can help staff more efficiently address questions and implement solutions.

- Consider how innovations to UI systems could address future emergency-based influxes of claims. A national template for emergency unemployment compensation that states could implement into their systems, for example, would help states avoid having to write whole new programs. Creating this template requires longer-term strategic thinking about standardizing changes in eligibility and payment rules to enable states to react much more quickly and efficiently in an emergency.

When a public health crisis disrupts our daily lives, as we’re seeing now with COVID-19, states often struggle to implement new rules imposed on the UI program by the federal government—as we saw with the Great Recession. Linking federal dollars to modernizing UI policies and systems goes a long way to help states adopt new rules and adjust their systems. As demonstrated by this review of unemployment compensation provisions under the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, research shows that states specifically weighed the value of the potential federal incentives against the costs—both in terms of administrative burden and in terms of additional benefit payments—before deciding to adopt the new policies. As such, ongoing state, federal, and local collaboration will be critical to processing many new claims.

COVID-19 has highlighted some difficult truths about how we manage safety net programs like UI during a public health crisis. One of those truths is that we are not as prepared to respond to this significant and unprecedented strain on the UI system as we need to be. Just one month ago, for example, several states anticipated a decline in claims. Some even needed fewer staff and less resources to maintain daily operations. In just a matter of days, that’s all changed. The crisis we face now is littered with unknowns. It requires all of us—policymakers, program administrators, economists, researchers, workforce development experts, and others—to band together, digging deep into our knowledge and experience to collectively progress through this crisis together.

To learn more about Mathematica’s employment policy research, visit our website.