The early grades lay an important foundation for students’ future academic success. Yet not a single state systematically measures how well its schools support students’ academic growth in the earliest grades, from kindergarten through grade 3. Nearly all states administer the first statewide standardized assessments at the end of grade 3, which means that grade 4 is the earliest point at which student growth can be measured. As a consequence, for a K–5 elementary school, student-growth measures used to assess performance include only two of six grades. Making student growth in early elementary grades more visible could powerfully inform educational investments, policies, and practices.

To better understand its schools’ contributions to students’ learning in the first four grades, the Maryland State Department of Education partnered with the Regional Educational Laboratory Mid-Atlantic to explore constructing a school-level growth measure for kindergarten to grade 3.

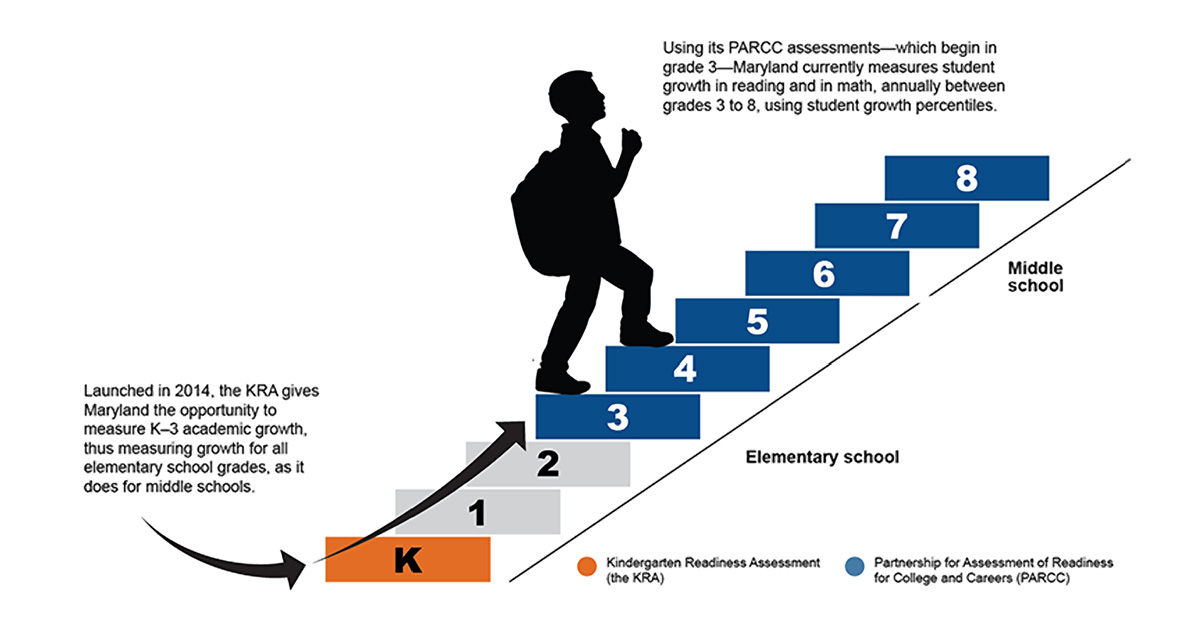

The new measure could help Maryland by informing policy decisions and resource allocation to improve early learning. It could also ensure the state’s accountability system reflects students’ growth in all elementary grades, as is the case for middle schools. This effort builds on the state’s 2014 launch of the statewide Kindergarten Readiness Assessment (KRA), which it administered to every kindergartener at the start of the 2014/15 school year. The KRA provides a baseline measure of school readiness at the point of kindergarten entry and a reference point for measuring K–3 growth.

Lighting the path forward

The study measured students’ growth in reading and math using the KRA and grade 3 Partnership for Assessment of Readiness for College and Careers (PARCC) assessment. The approach, based on student growth percentiles, is similar to what Maryland currently uses for later grades. The study team examined the validity and precision of the school-level growth measures.

In short, we found that the KRA and PARCC can estimate schools’ contributions to student growth for grades K–3, filling a critical gap in the state’s knowledge about its elementary schools’ performance. We did find some reasons for caution, however, in using K–3 growth measures for accountability purposes:

Validity: Is the growth estimate credible? Does it appear to be measuring what it is intended to measure: schools’ true contributions to their students’ K–3 growth? Are the assessments used in the model measuring similar aspects of student academic performance?

Precision: Is the growth estimate a consistent measure? Will schools’ estimates vary from year to year even if their true performance is not changing?

- The KRA and PARCC can estimate schools’ contributions to student growth for grades K–3, but the measures might be less valid than those used in later grades. The strength of the relationship (that is, the correlation) between students’ KRA and grade 3 PARCC scores is smaller than correlations between students’ PARCC scores in later grades. A weaker relationship between the scores makes it harder to produce a valid measure of growth. This could be an inherent challenge with early learning measures. If so, states could acknowledge these differences by assigning less weight to the K–3 growth measure in their accountability framework relative to growth measures in later grades or by publicly reporting K–3 growth without incorporating it into an accountability system.

- Schools’ K–3 growth estimates are less precise for smaller schools than for larger ones. For example, math estimates for the smallest schools—those in the first percentile for size—are roughly one-third as precise as estimates for schools of median size. States interested in measuring K–3 growth for schools might want to ensure that decisions based on these estimates consider their precision. States can also improve the precision of these estimates by using methods such as empirical Bayes shrinkage or basing growth estimates on multiple years of data.

- Administering the KRA to a subset of students, compared with administering it to all students, greatly reduces the precision of schools’ K–3 growth estimates. A 2016 Maryland law gave local school systems the choice to administer the KRA to all kindergarteners or a random sample of kindergarteners, beginning with the 2016/17 school year. We found that this sampling approach will greatly reduce the precision of schools’ growth estimates. States interested in measuring K–3 growth should consider this information as they weigh the costs and benefits of using sampling to administer assessments.

A blueprint for measuring early growth

Overall, the findings suggest that states with comprehensively administered kindergarten entry assessments have a real opportunity to understand how individual elementary schools contribute to their students’ learning in grades K–3. Other states interested in tracking their schools’ contributions to early learning can build on Maryland’s experience of developing a growth measure that uses two different assessments administered multiple years apart.

The methods used in this study provide states with a blueprint for examining the validity and precision of K–3 growth measures and for monitoring these properties over time as future student growth data becomes available and new assessments are introduced. Maryland, for example, is replacing the PARCC assessments with a new statewide assessment this year, so the state will be able to use this study’s methods to assess how the validity and precision of the measure changes under the new assessment.

At REL Mid-Atlantic, we’re committed to working with our stakeholders to assess the best ways to measure school-level growth in the early grades and apply what we learn to improve students’ outcomes. Students enter the classroom with diverse backgrounds and skills, and measuring students’ growth in early elementary grades has the potential to provide information decision makers need to develop policies and inform practices that improve instruction for all children.

Cross-posted from the REL Mid-Atlantic website.