The academic achievement gap in the United States is large. A low-income child has less than a 1 in 10 chance of graduating from college, compared to nearly 8 in 10 high-income children. High-income children dramatically outperform low-income children in school, resulting in educational inequality that mirrors broader income and wealth gaps in our county.

What might explain this inequality? Are low-income children taught by less effective teachers than high-income children? There is evidence that low-income students are more likely to have less qualified teachers—defined as those lacking experience, certification in the subjects they teach, or a master’s degree—despite federal policies that discourage this. Yet a wide range of studies suggest that teacher qualifications are not a good indicator of teacher effectiveness. What about access to effective teachers? Our recent research for the U.S. Department of Education’s Institute of Education Sciences (final report here) examines this issue.

Do Poor Students Have Less Effective Teachers?

Using five years of data from 26 large, economically diverse districts around the country, we compared the effectiveness of high- and low-income students’ teachers. We focused on fourth- to eighth-grade students and their English/language arts and math teachers. In these districts, we confirmed previous research showing that teachers matter: we found large differences in how effective teachers are in raising student achievement.

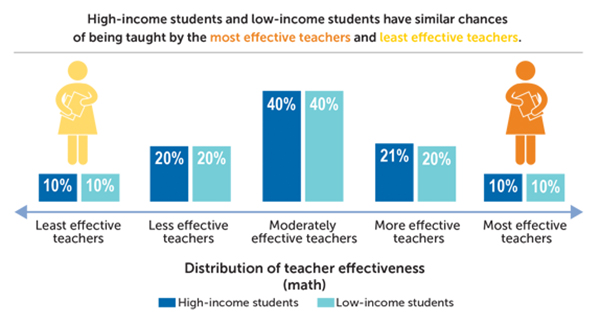

But surprisingly, the typical low-income student had a teacher nearly as effective as the typical high-income student. Overall, the two groups of students had roughly the same mix of teachers in terms of effectiveness. High- and low-income students were just as likely to have the most (and the least) effective teachers. In short, the distribution of teachers in these districts was nearly equitable—with small differences in effectiveness for the two groups. These differences were so small that eliminating them—so that high- and low-income students had teachers of identical effectiveness from fourth to eighth grade—would not substantially reduce the student achievement gap.

A few districts exhibited meaningful teacher inequity. These districts were the exception rather than the rule, however. More commonly, high- and low-income students had similarly effective teachers.

Closing the Achievement Gap

How can this be, given such large gaps in high- and low-income children’s achievement? One possible explanation is that differences in children’s home and neighborhood environments before they enter school drive inequality in educational outcomes. A half century after the Coleman Report concluded that “differences between schools account for only a small fraction of differences in pupil achievement,” researchers have found that large achievement gaps between high- and low-income children exist at the time of kindergarten entry and do not appear to grow substantially larger as children progress through school. This suggests that what children bring with them into school, along with disparities in access to high-quality pre-K or other educational resources outside of school, may be more important than teachers in explaining achievement gaps.

Although teacher equity policies are unlikely to eliminate student achievement gaps overall, we think there is a role for education policy in reducing inequality in educational outcomes. For example, teacher equity policies may be helpful in districts that exhibit meaningful inequity—such as in the small number of districts in our study where we found greater levels of inequity. To determine whether teacher equity policies may be helpful, districts should assess their own situation by measuring whether their low-income students have equal access to effective teachers (and can use publicly available programming code downloadable from the Educator Impact Lab’s site to measure teacher impact and effective teaching gaps if they choose). Policies that address the distribution of teachers have potential to narrow the student achievement gap in districts with greater inequity. For example, districts could implement policies designed to influence the quality of teachers hired into high-poverty versus low-poverty schools, or teacher transfer patterns between schools.

To make a dent in achievement gaps in districts without meaningful inequity, policymakers could go beyond providing low-income students with equally effective teachers and aim for providing much more effective teachers than those available to their high-income peers. For example, incentives could encourage highly effective teachers to work in high-poverty or low-performing schools. Mathematica recently studied a program that offered $20,000 bonuses to highly effective teachers who moved into the lowest performing schools for two years, and this effort improved test scores in the elementary grades.

A variety of other policies could lead to high-poverty schools having more effective teachers than low-poverty schools. For example, districts could implement policies focusing on teacher recruitment and hiring, transfer and retention, or training and professional development. Alternatively, policies could aim at whole-school reform in high-poverty schools. Although there is no research consensus on which policies might work best to improve the effectiveness of low-income students’ teachers, districts can tap relevant resources to move ahead. For example, the What Works Clearinghouse, operated by Mathematica for the Institute of Education Sciences, summarizes evidence on the effectiveness of a wide range of education interventions.

True progress in reducing inequality in educational outcomes may be possible, but our study found little support for the premise that low-income students struggle mainly because they have less effective teachers.