The field of economics seeks to answer the question of how best to allocate scarce resources. When I was 22 years old and working full time in an emergency soup kitchen, I experienced this scarcity every day. We provided lunch to more than 300 people in three hours in a 30 square foot room, a nearly impossible feat. Food was scarce and we worked hard to allocate what we had to meet the needs of all of the families we served. The afternoon was the toughest time of the day—there were 10 people in line and only four meals left. As a soup kitchen worker, I wanted to help everyone, but the economist in me kept asking: what’s an optimal allocation in this situation?

Fast forward almost two decades and, as a social science researcher, I’m still trying to find optimal allocations of scarce resources. Rather than divvying up meals, my colleagues and I help our clients use data to allocate their scarce resources to plan and run programs in the most effective way possible.

In our recent work with the Massachusetts Housing & Shelter Alliance (MHSA), we looked at one of its programs that provides permanent supportive housing for 500 to 800 homeless people in the state. It’s part of a Pay for Success initiative that works to allocate limited housing spots and scarce public spending on emergency services by providing housing to the costliest segment of the homeless population—those that will incur the largest health care costs associated with remaining homeless.

At the center of the program is a triage assessment tool used by MHSA provider member staff at emergency shelters and health services organizations to collect data about the homeless community they serve, including demographic characteristics, homelessness history, use of emergency services, physical health, mental health, and substance use. The triage assessment tool then assigns a score based on these responses, which MHSA uses to rank people based on their likelihood of being frequent users of emergency health services, and returns the ranked list to providers. As housing units become available, providers use the rankings to determine who should get priority access.

Given the stakes, MHSA wanted to be sure that the triage assessment tool was actually a good way to identify the clients who are likely to need the most—and costliest—help, and who would also benefit the most from access to permanent housing.

To help MHSA answer whether the triage and assessment tool was functioning as intended, we studied administrative data on the triage scores and data on subsequent service use reported by chronically homeless people in Massachusetts.

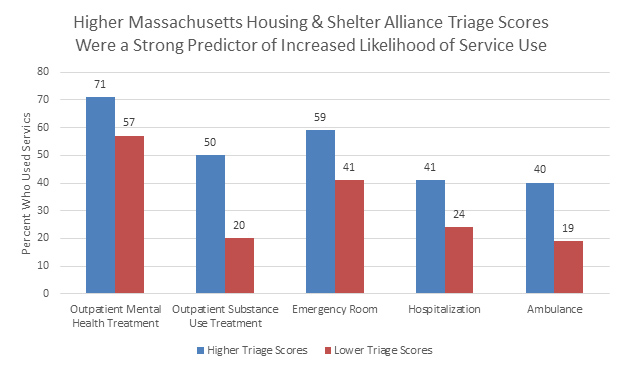

We found evidence that the triage scoring metric is a strong predictor of subsequent service use.

People who received a higher score during the triage and assessment interview were more likely to use most of the emergency services we examined in the months following the assessment interview. Those emergency services include some that are costly to the public, such as outpatient mental health and substance abuse treatment, emergency room visits, hospitalization, ambulance use, and stays in detoxification centers. The differences in the likelihood of using services were particularly large for several outcomes, such as outpatient mental health treatment (71 percent among participants with a higher triage score compared with 57 percent of participants with a lower score), outpatient substance use treatment (50 versus 20 percent), emergency room use (59 versus 41 percent), hospitalizations (41 versus 24 percent) and ambulance use (40 versus 19 percent).

Although MHSA is still evaluating the cost effectiveness of the broader Pay for Success initiative, our study findings suggest that the triage and assessment tool is successfully attempting to allocate scarce resources by effectively identifying chronically homeless people who will be frequent users of emergency health services if they remain homeless.

This exciting project brought together my own personal history working on the front lines as a direct service provider for chronically homeless people and my subsequent methodological training as an economic researcher. It also synthesized two core components of the work we do each day at Mathematica: producing high quality, rigorous, and objective research to improve public well-being and working with local organizations like MHSA to assess day-to-day program operations to improve people’s lives as cost effectively and as quickly as possible. It’s a powerful example of helping clients use the information they have to find the best allocation of scarce public spending and other resources.