In his two decades as a life coach, Kentrell Killens has had guns pulled on him and a client when they were in the car together. He has been put in a police vehicle—more than once—for not divulging information to police about a client. He’s also been written up by police and probation officers for siding with clients.

Despite the stresses that often came with counseling young people in Oakland with prior involvement in the juvenile justice system, Killens has always found purpose in providing the assistance that he himself couldn’t find as a teenager.

“It was personal for me. I grew up with individuals who made promises about stuff and never really could come through on their promises. I was a kid who was left on the porch with my bags, waiting on my cousins who were supposed to be coming and never came. I decided that I was going to be that guy who came for the people who needed me,” he said. “I didn’t want young people to feel the way I felt: left out and not having the support that I needed.”

Killens is one of five people featured in the latest episode of On the Evidence, which focuses on a violence reduction strategy that Mathematica is evaluating. Find the full episode below.

The City of Oakland assigns life coaches to youth at high risk of violence. Life coaches draw from personal experiences that are similar to those of the clients they’re mentoring. Together, they set goals related to exploring employment and educational opportunities as well as reducing future involvement with law enforcement. The city is working with Mathematica to evaluate the youth life coaching strategy and other violence reduction programs—including life coaching for adults—housed under a larger initiative called Oakland Unite.

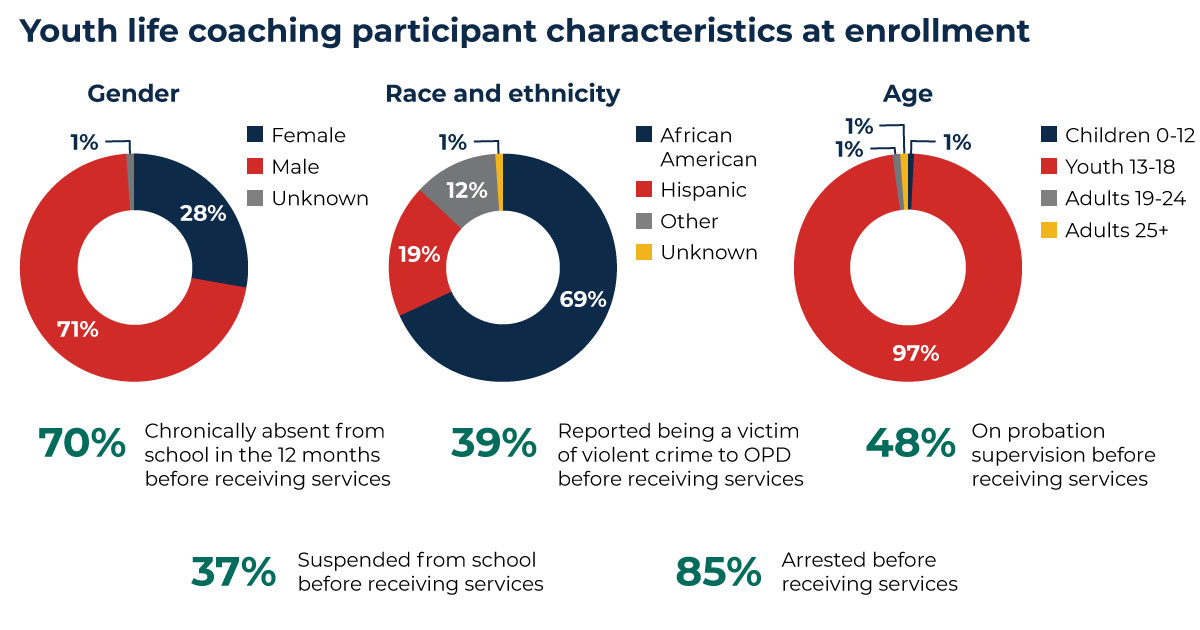

Many of the clients—who range in age from 13 to 19—have been suspended from school, arrested, and put on probation. Many of them have been shot or had family members who were murdered. Oakland Unite’s life coaching strategy attempts to transform their lives through intensive relationships with peer professionals.

Source: Administrative data from Oakland Unite, Alameda County Office of Education, Alameda County Probation Department, Oakland Police Department, and Oakland Unified School District.

Peer professionals are “people who are not necessarily clinicians but who actually share similar life experiences, who reflect the communities and the experiences that our participants live in or go through,” said Peter Kim, who manages Oakland Unite. The life coaches “are trained in how to be mentors, but also [how to be] coaches to help navigate through the systems that our participants have to go through: everything from probation and the courts to the school systems, how to get a job, how to navigate employment training programs and transitional employment to find the actual, permanent job.”

On average, Killens would see as many as 12 clients in a day. For each person on his caseload, he would meet with them face-to-face twice a week. Outside of those meetings, he would advocate for them with local government agencies, such as the courts, the probation department, or family services. The first meeting can take a couple hours and involves a lot of paperwork, but then the life coach and client start to make plans and set goals together using a format called a life map. They identify their roles and responsibilities associated with managing each goal, as well as people in the client’s life whose support would be necessary for achieving a goal.

Life coaching, Killens explained, is “an opportunity to not plan what we think is in the best interest of the client but to allow a conversation to define what they think is best for them, and what they’re actually ready to put the energy into.”

The lived experience of Oakland Unite’s life coaches might be a key ingredient for the program’s success, but it also presents challenges for grantee agencies that need to recruit and retain people with the right skill set and background. Most of the agencies that provide life coaching for Oakland Unite told Mathematica that they had experienced high staff turnover, which they attributed to a range of reasons, including their inability to match the salaries offered by other organizations, the high cost of living in the Bay Area, and the stressful and dangerous nature of the life coaching position.

“Not everybody can do this. Not everybody has the heart to do it. Not everybody has the relationships to do it,” Killens said. “I tried to make sure that I kept myself grounded, and I remembered the impact: when you can look at a young person and see yourself and think, ‘I was headed down that same path, but then look where I’m at now.’”

A 2019 report from Mathematica found some promising signs that life coaching is helping clients make progress on criminal justice and education goals, but there were disappointments as well.

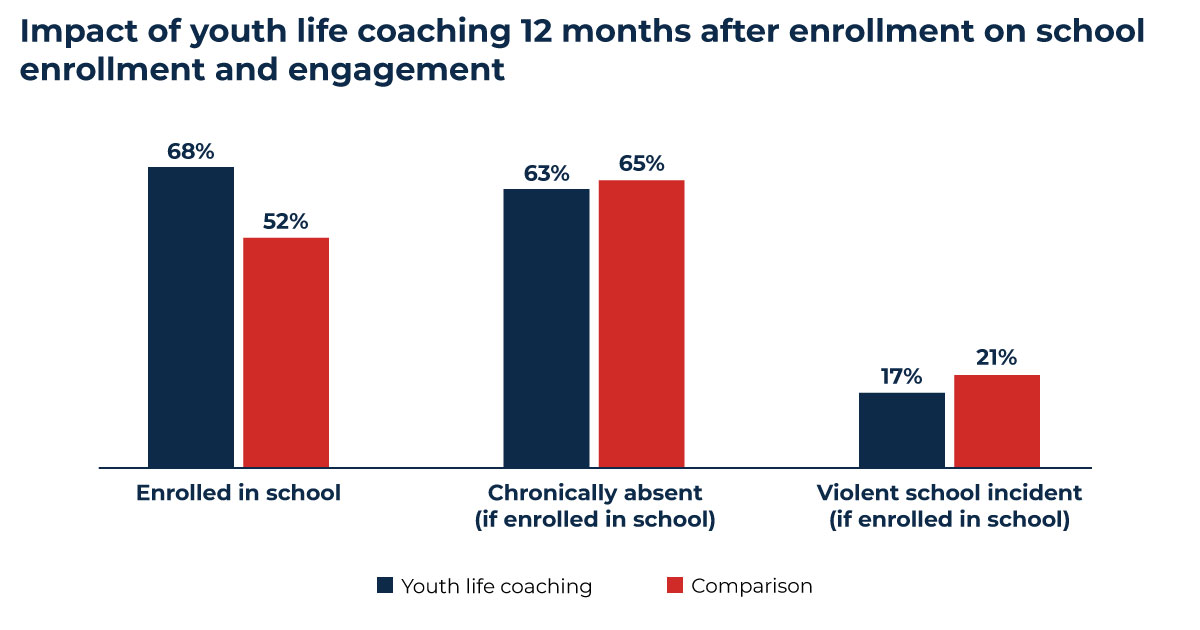

In terms of criminal justice outcomes, when Mathematica looked at arrests for life coaching participants in a 12-month follow-up period and compared them with arrests for similar youth who did not receive those services, the arrest rates appeared about the same. In other words, exposure to life coaching didn’t seem to have reduced arrests. However, further analysis did show that the youth life coaching participants were about 3 percentage points less likely to be arrested for a violent offense in the six months after beginning services.

In terms of education outcomes, relative to the comparison group, school-aged life coaching participants were 16 percentage points more likely to be enrolled in school in the 12 months after starting services. Naihobe Gonzalez, a senior researcher at Mathematica in the Oakland office, explained that the increase in school enrollment is a direct result of how the life coaching strategy is designed to promote effective cross-agency collaboration.

“Part of the Oakland Unite youth life coaching model is that there’s a staff person from the school district who sits at the youth detention center and ensures that students are being reenrolled in school as they’re leaving, and tries to make sure that they’re being reenrolled in a school that is convenient and safe for them,” Gonzalez said. “That reenrollment process is baked into the Oakland Unite model.”

Source: Administrative data from Oakland Unite, Oakland Unified School District, and Alameda County Office of Education.

Beyond the encouraging education and criminal justice outcomes, another sign of the strategy’s positive effects is the participants’ own personal assessments of working with life coaches.

More than three-quarters of surveyed life coaching participants said they agreed or strongly agreed that their situation is better because of the Oakland Unite services.

When asked what they thought their lives would be like one year in the future, the vast majority of respondents expressed positive outlooks. All survey respondents indicated that it was likely or very likely that they would have a safe place to live, avoid unwanted contact with the police, and be able to resolve conflicts without violence. At least 90 percent noted that they would likely or very likely finish their education, be more hopeful about life, be better able to deal with a crisis, avoid unhealthy drug or alcohol use, have a steady job, contribute to their community, have stronger relationships, and resolve their legal problems.

One participant, who asked not to share his name, said that his life coach helped him get an apartment and go back to the doctor for regular checkups. If not for the life coach, he would probably be homeless, he said. Those are discrete and tangible impacts, but the participant also mentioned the benefit of a long-lasting relationship with someone who has his best interests at heart.

“He’s not really even my life coach anymore, but if I call him and tell him I need him, he’s going to come,” he said. “It’s like, we are family now.”

Another participant, Anayeli Vega-Gonzalez, credits her relationship with her life coach with helping her attend school more often, earn a 4.0, get on the honor roll, secure internships, and get off probation.

If she didn’t have her life coach, “I think right now, I could probably be dead or also in jail,” Vega-Gonzalez said. “It’s gotten me out of the streets. It’s gotten me out of the violence that I was living in in my neighborhood. It’s keeping me going to school and [completing] the goals that I have, such as graduating and getting into college.”

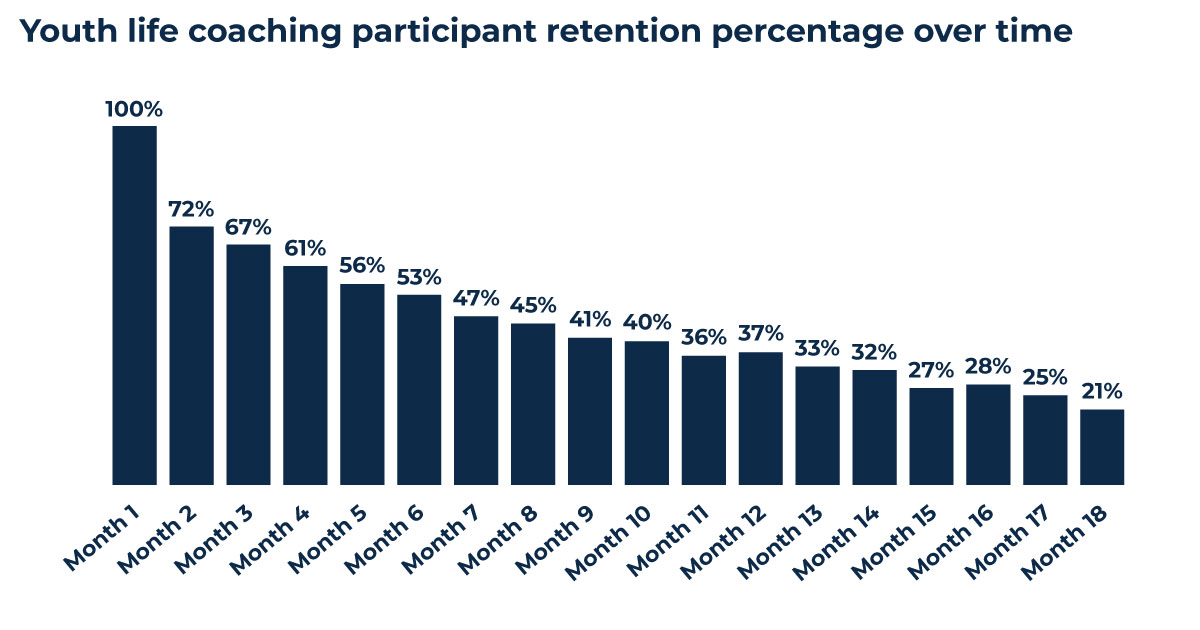

Although Vega-Gonzalez and the other participant are examples of life coaching success stories, the data show that some of the people who initially receive life coaching services don’t continue with the program. More than a quarter of participants drop out after the first month. Retention continues to decline a little each subsequent month, but the biggest drop is between the first and second month.

Source: Cityspan data.

“It doesn’t surprise me,” Killens said. “I think a lot of people are not ready for this intense level of self-discovery. It’s scary to have to unlearn behavior and relearn new ways of trying to do life. For some, it’s just more comfortable to remain who they are than it is to address this idea of change. And then there are some who are so deep into street life, nothing that we said has actually penetrated yet.”

Data from Mathematica’s evaluation show that between 36 and 40 percent of youth who drop out eventually reengage.

“There are a good number of folks who come back and are successful even after leaving,” Killens said. “I think the importance of the relationship with a life coach is that the door is open because it’s really about what the client is ready to do and not what we think is best for them. When they’re ready to work, we are here. Sometimes they have to keep falling. Sometimes they haven’t hit that bottom yet.”

One feature of the life coaching strategy that might be of interest to policymakers in other municipalities is the use of financial incentives to motivate participants to hit personal milestones. At least one other U.S. city—Richmond, California—uses financial rewards as part of a larger strategy to reduce violence, and other jurisdictions have considered implementing a similar approach. With Oakland Unite’s life coaching strategy, financial incentives are baked into the goals set by the participants and their coaches.

Small goals, such as getting a driver’s license or showing up consistently for coaching appointments, might earn $25 or $50. Larger goals, such as applying to 10 jobs in a month or completing an anger management course, might earn $400. Life coaches use a standardized tool to assess what a milestone should earn.

The Mathematica evaluation didn’t attempt to quantify the effect of financial incentives alone on program participation or specific criminal justice and education outcomes, but interviews with life coaches suggest that the program does help with early engagement.

“What we’ve heard from life coaches is that the incentives are really pivotal in helping participants become interested initially and in motivating them to reach their goals,” said Gonzalez, the senior researcher at Mathematica. “At the same time, we’ve heard that there comes a point where they’re just engaged, and the incentive isn’t the main reason why they’re participating.”

Life coaches also told Mathematica that the funds for financial incentives were too low or ran out too fast. Funding for financial incentives represents only 13 percent of the overall life coaching budget. The incentives are designed to be small nudges that motivate behavior change, not a sustainable source of income. Ultimately, the draw for participants should be the relationship with a life coach, not the financial incentives, said Peter Kim of Oakland Unite.

“It really isn’t meant to substitute for actual earnings. It’s nowhere close to what someone needs to actually live here in the Bay Area. It really is just a form of recognition to say, ‘Hey, I see the amount of work that you’re putting into this life plan of yours, and I recognize the effort, and this is a symbolic gesture to let you know [that] I appreciate you.’ They appreciate that themselves, but it does something for someone’s self-esteem when they have money in their pockets to bring groceries home or pay for that birthday gift for their loved one or for their own child and not have to ask someone else for a loan.”

Because of COVID-19, life coaches transitioned in March to remote sessions while Oakland residents sheltered in place and practiced social distancing. It’s unclear what, if any, effects the pandemic might have on the model’s effectiveness. However, Mathematica and Oakland Unite continue to study youth life coaching to understand what is effective about the current strategy and how it can be improved.

One future area of research will focus on the length of time that participants stay engaged with their life coaches. It’s possible that the results in the 2019 report underplay the program’s true impact because they only pertain to youth who participated in at least 10 hours of life coaching. In other words, the results shed light on life coaching’s effects on youth who receive at least some exposure to the program. Because the program is currently designed for 12 to 18 months of frequent engagement, future research will examine what happens to the subset of participants who benefit from help for longer stretches of time, as intended.

Want to hear more episodes of On the Evidence? Visit our podcast landing page or subscribe for future episodes on Apple Podcasts or Spotify.

Show Notes

For more information on the partnership between Oakland Unite and Mathematica, find the project page here.