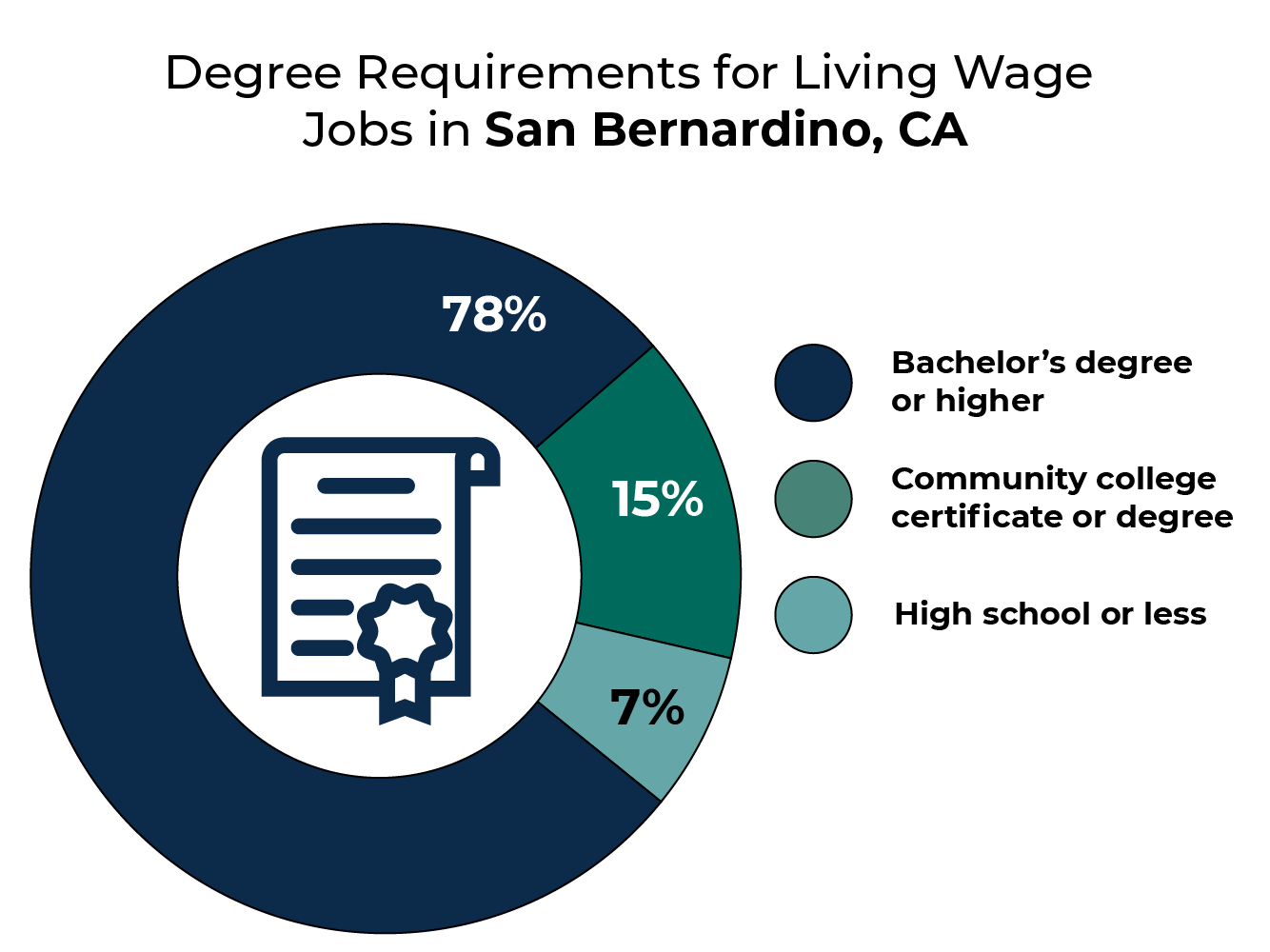

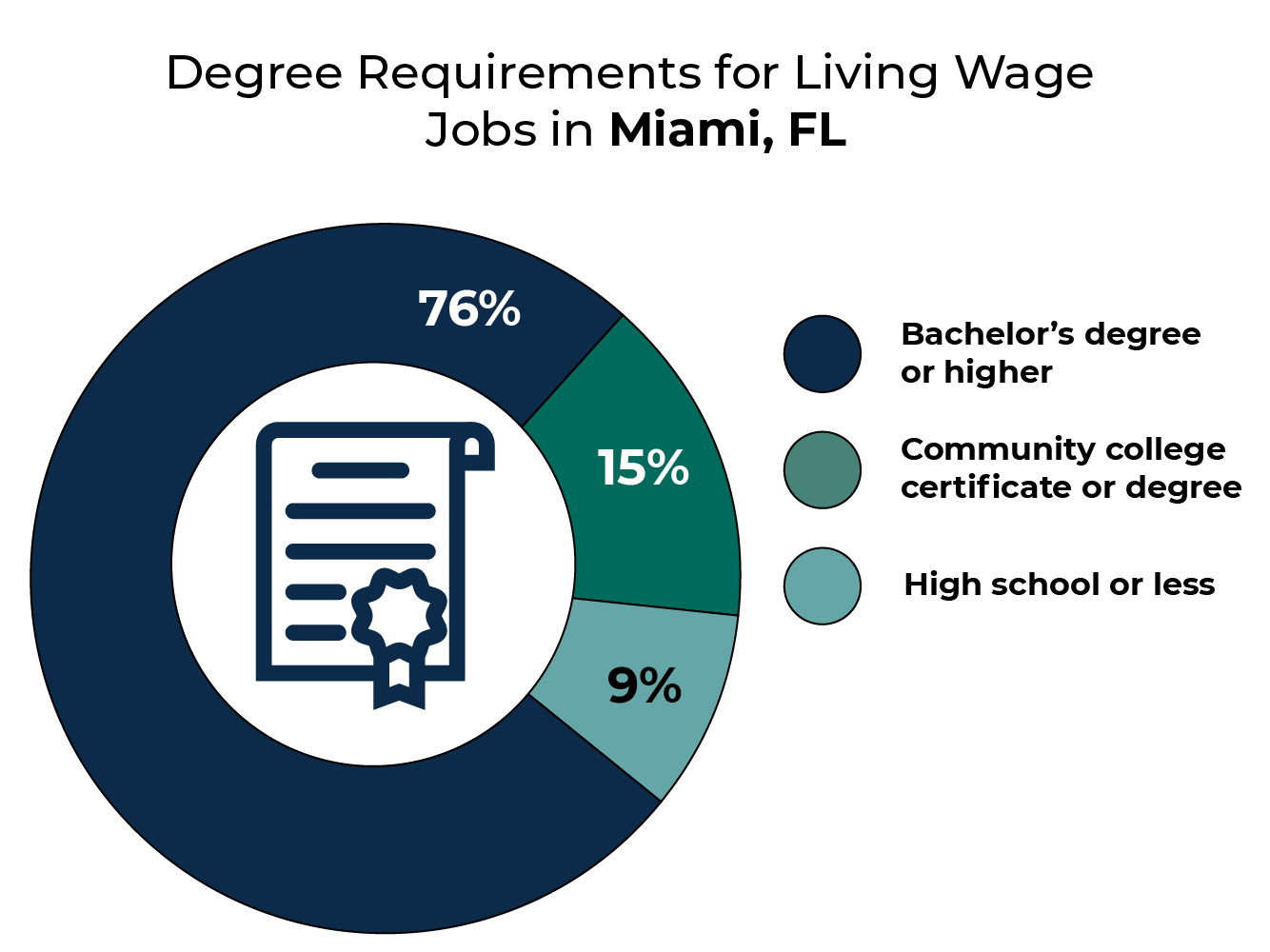

Despite growing public sentiment that college may not be worth the cost, educational attainment continues to be a primary predictor of economic stability. That’s because most jobs that pay a living wage require bachelor’s degrees. In communities from San Bernardino, California, to Miami, Florida, the vast majority of the jobs paying a living wage require a bachelor’s degree or more.1 However, stark disparities in educational attainment between racial and ethnic groups, as well as by gender and economic standing, reinforce the inequitable distribution of wealth and opportunity. One way to address the gap between perception and opportunity—and to ensure equitable access to these opportunities—is to use state longitudinal data systems to quantify the factors that influence which pathways students take, what degree or credential they earn, and how that training relates to their employment and earnings outcomes.

When it comes to designing equitable college and career readiness policies, context matters. From decades of research on inequalities in schooling, we know that students’ educational trajectories are not solely a function of individual choices. They are shaped by the classroom, school, and neighborhood conditions in which students learn. Yet today’s students learn within highly stratified educational systems, in which racial and economic segregation is on the rise and access to rigorous curricula, high-quality postsecondary pathways, and prosperous careers remains out of reach for many. This stratification of opportunity begins early and compounds as students progress through their educational journeys. The practice of tracking students into different classes and course sequences based on their perceived abilities, for instance, can influence their subsequent access to advanced coursework, their college-going behaviors, and the types of jobs available to them.

State longitudinal data systems provide some of the information necessary to shed light on the relationship between school and work. However, their current focus on fulfilling federal and state reporting requirements means they often lack context that could be used to help address structural inequities and help more students attain living wages. Therefore, the Education-to-Workforce Indicator Framework (E-W Framework) recommends that states collect and report a set of 99 indicators across the pre-K-to-workforce continuum that are associated with people reaching economic mobility and security (see this blog post for a more detailed description of the E-W Framework).

There are several steps states can take, either independently or together, that would enable longitudinal data systems to provide a more holistic picture of the opportunities available to students.

Linked data sets should be expanded to include existing data that go beyond accountability requirements

Education institutions and state agencies are already capturing some of the indicators the E-W Framework recommends, but those indicators are not yet included in linked data sets. For example, many agencies document student-specific items like consistent K–12 attendance, concentrations in high school career and technical education pathways, and accumulation of first-year college credits. These data points could help clarify critical milestones in education pathways that may predict how long students stay in school or what they study. State data systems could also be expanded to document structural factors that may drive inequitable resource allocation within education systems such as educator retention, expenditures per student, and cumulative student debt. Community members, policymakers, and state agencies can work with the governing boards of state longitudinal data systems to encourage the integration of these additional data points and to provide broader access to this information so that they can advocate for interventions while students are still enrolled and address disparities in the resources available to students.

New types of data collection are also needed

Other data points may be more challenging to collect, but these issues are not insurmountable, particularly if states invest in solutions that are made available to all students or if they work together to address common challenges.

Implement school climate surveys. Many of the measures must be collected directly from students, particularly related to factors such as mental and emotional well-being, self-efficacy, and school safety. Schools could best address this by using a single survey at the state level, such as the California Healthy Kids Survey. California school districts use this information to meet funding and planning requirements related to improving school climate, student engagement, parent involvement, and academic achievement.

Begin collecting data on additional types of programs. Other E-W indicators reveal gaps in data collection, particularly participation in noncredit community college programs. Some states, including California, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Louisiana, and Texas, are already collecting noncredit data and linking them to other data sets to learn whether students transition from noncredit to credit pathways and whether their earnings increase. For example, California makes this information publicly available through the Adult Education Pipeline dashboard, which helped inform a set of reports from WestEd’s Center for Economic Mobility that recommend ways to improve transitions out of noncredit programs.

Build partnerships to gather supplementary information. Another important data point related to career outcomes is the impact of earning an industry-recognized credential. Given recent investments in creating short-term training that is more responsive to employers, gathering this information could help identify whether state funds are supporting people in attaining a living wage. Some states like North Carolina link information on state licensure attainment with community college data. This complements efforts by the National Student Clearinghouse to compile credentials issued by professional associations, such as for advanced manufacturing.

Create common data definitions. Some data points would benefit from establishing a singular definition, particularly for essential workplace competencies like communication, higher-order thinking, and digital skills. Curriculum available through the Essential Skills Program and tools like Design Lab’s 21st Century Skills Micro-Credentials can help teach and assess these skills. Data on attaining skills badges and micro-credentials can then be included in state longitudinal data systems.

Action is needed at the federal level

In two cases, federal action is needed to integrate E-W indicators into state data systems. Some parties have interpreted language from the Higher Education Act, which establishes the appropriate uses of financial aid data, as precluding financial aid data from being included in research projects or longitudinal data systems. Furthermore, no data sharing agreements currently allow states to match student records to determine whether individuals entered military service. Data champions can encourage the U.S. Departments of Education and Labor to issue guidance that authorizes state longitudinal data systems to include financial aid and military records. Such a step would help the field better understand how financial aid and military service provide pathways to education and employment, particularly for low-income populations and people of color.

A call to joint action

States can develop a more holistic picture of the contexts surrounding students’ educational trajectories, in service of designing equitable policies that expand, rather than foreclose, the opportunities available to them. If diverse interest holders such as policymakers, educators, employers, and workforce development organizations have a joint understanding of the contextual factors shaping students’ college and career readiness, they can work together to create pathways and supports that lead to living-wage jobs.