“When you have everybody reduced to numbers, it doesn’t create a good atmosphere, it doesn’t help teachers teach, and it doesn’t help children learn.”

That’s what Arizona elementary school teacher Lauren D’Amico told The Atlantic in a 2015 story on high-stakes educator evaluation systems, which assign consequences such as performance pay or dismissal based on a set of performance measures—some of which are based on student test scores. D’Amico’s negative views on teacher evaluation are shared by many other teachers, including nearly half of the National Education Association members, who said in a survey that they had considered leaving the profession because of standardized testing. The Georgia Department of Education placed much of the blame for a teacher “dropout crisis” on testing and evaluation.

So, does high-stakes evaluation scare teachers away? And if so, which teachers? Does this help or harm students? Is it time to sound the alarm, as the Georgia Department of Education has done? High-stakes evaluation does affect who comes into the classroom and who stays there, and research indicates that this flux may actually be good for students.

Accountability deters some teachers

Evidence shows that many potential teachers dislike high-stakes evaluation enough to switch careers before they even enter a classroom. According to a recent study led by teacher labor market expert Matthew Kraft, the supply of new teachers—indicated by the number of new teacher licenses granted—falls when a state implements a high-stakes evaluation system. Would-be teachers presumably follow other career options to avoid getting a bad evaluation and facing dismissal or being passed over for a performance bonus. Or they may not want to do what it takes to get high scores on evaluation measures. Whether it’s a false choice or a real trade-off, a prospective teacher might feel forced to choose between teaching according to his or her ideals or preparing students for standardized tests.

High-stakes evaluation also influences established teachers’ decisions to leave the profession or move to another state or district with lower stakes. According to a Learning Policy Institute (LPI) report, 25 percent of those who left teaching, like those in Georgia, cited assessments or accountability pressures as contributing factors.

Teachers scared away may be the least effective ones

The teachers kept out of the profession by high-stakes evaluations did not appear to have more potential to be effective than those who stayed, but it is difficult for researchers to measure teachers’ potential before they step into the classroom. Kraft and his co-authors showed that teacher supply dropped when the evaluations were implemented, but the researchers had limited information about the qualifications of teachers, relying on measures of the selectivity of the universities granting the teaching degrees. They found no strong evidence that high-stakes evaluation lowered these qualifications. However, as the researchers acknowledge, this is hardly conclusive evidence that high-stakes evaluation pushes out both effective and ineffective teachers equally. Teachers’ qualifications based on their background and training are not predictive of their effectiveness in the classroom.

Regarding leavers—teachers who leave the profession—it may be the weakest teachers who are put off by accountability. While the LPI report suggested that a quarter of Georgia teachers cited assessments or accountability pressures as reasons for leaving, the corresponding number in the District of Columbia Public Schools (DCPS) was lower—10 percent—and teachers who cited these same reasons, in a survey of departing teachers over a three-year period, tended to be lower performing.

Evidence from controlled studies with comparison groups also suggests that these factors impact less effective teachers the most. One study used a regression discontinuity design to compare outcomes for DCPS teachers with IMPACT scores just above or just below the cutoff for being rated ineffective, which carries a risk of dismissal. The study showed that the DCPS IMPACT evaluation system pushed out low-performing teachers at risk of dismissal for being rated ineffective, but it may not have affected other teachers.

Although the study’s research design leaves open the possibility that IMPACT lowered the retention of all teachers across effectiveness categories, the overall retention rate of DCPS teachers actually increased the year after IMPACT was rolled out. Also, in 10 other districts included in another rigorous study, which randomly assigned schools to offer or not offer pay-for-performance bonuses based on evaluation scores, teacher retention rates rose.

Students win

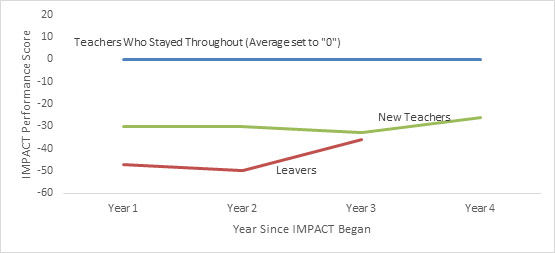

High-stakes evaluation does put off some teachers, but does it harm students? According to findings, students may actually benefit when lower-performing teachers leave if they are replaced by better ones, or if positive incentives such as performance pay motivate teachers to improve. The evidence from DCPS (see figure) and from Teacher Incentive Fund districts suggests that high-stakes evaluations with performance pay incentives can improve student outcomes. Some other experimental studies of performance incentives for teachers have not found benefits for students, but the incentives in these studies were often smaller than those given in DCPS and Teacher Incentive Fund districts.

DCPS replaced leavers with better teachers

Source: “Longitudinal Analysis of DCPS Teachers” Table IV.1

Note: Although both new teachers and leavers were less effective, on average, compared to the core group of teachers who stayed in DCPS, new teachers were more effective than those who left. Year 1 of IMPACT is the 2009-2010 school year.

Many teachers may dislike high-stakes evaluations, but such evaluations can improve student outcomes. Although they might push some less effective teachers or would-be teachers out of the profession, they may also direct these individuals toward more productive and rewarding careers. High-stakes evaluation scares away some teachers, but evidence suggests this isn’t always a bad thing.