In the United States, a range of social issues can negatively impact parenting, which in the worst of circumstances results in children entering the child welfare system. With the right structures in place, state and county child welfare agencies could work with caregivers to address a range of issues—from substance use disorders to housing instability to undiagnosed or undertreated mental illness—without having to separate families. If better services could be provided earlier, fewer families might need the more invasive intervention of the foster care system.

In 2018, Congress passed the Family First Prevention Services Act, commonly referred to as Family First, which redirects federal funding for child welfare services—formally known as Title IV-E reimbursement—to address families’ needs further upstream. Family First encourages the use of comprehensive, community-based approaches to prevent child maltreatment, promoting the idea that systems working in collaboration can accomplish much more than child welfare agencies operating in silos. The law creates an opportunity for states to receive partial federal reimbursement for some prevention services designed to reduce the need for foster care placement (including some mental health services, substance use disorder services, and parenting programs). The law also promotes the use of evidence-based practices by requiring that funded prevention services meet particular evidence-based criteria. However, shifting child welfare funding demands significant changes from states and counties in the course of a few years.

At the request of the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Mathematica interviewed states, counties, and organizations or consultants working with child welfare agencies to document how they are planning for Family First. We also comprehensively reviewed the financing strategies that states can use to fund prevention services. Based on our research, we developed a we developed a toolkit to help states prepare for implementing prevention services. Our work on the toolkit builds on our prior partnerships with states, counties, tribal communities, foundations, and the federal government to implement better ways of identifying children at risk of foster care placement before removal becomes necessary.

We understand that the logistical and administrative tasks before child welfare agencies are daunting, particularly amid the current pandemic, but they could also help protect more children from harm while keeping more families together. To ease the burden on state and local staff as they embark on this effort, here are six tips based on our research for the toolkit.

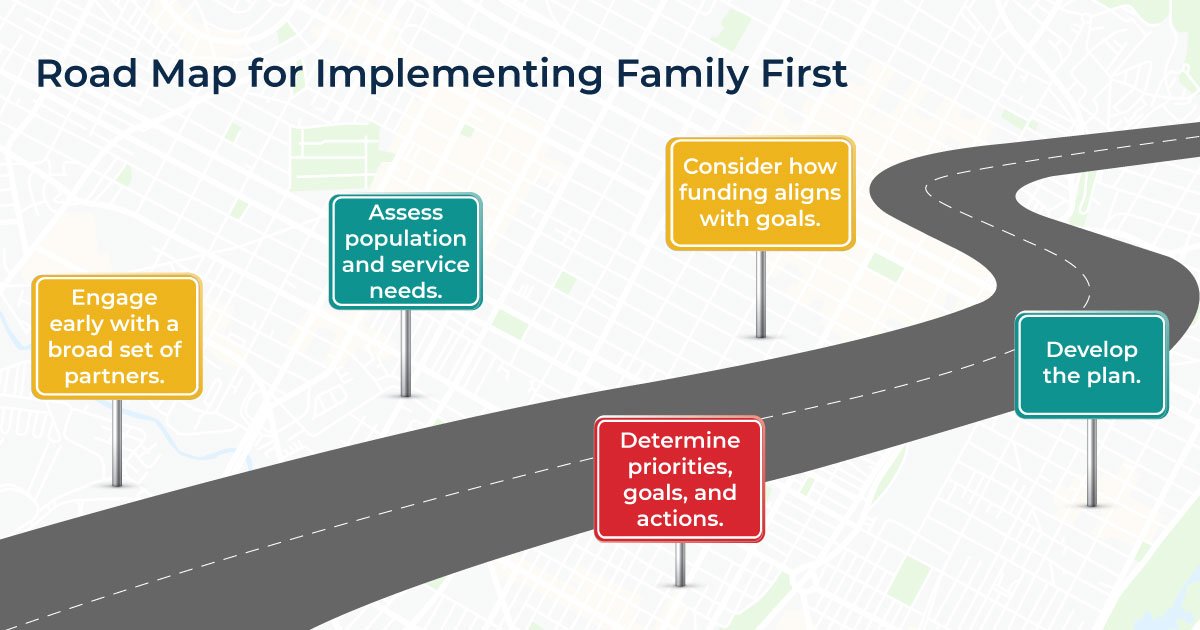

Start with a vision. It helps to start by putting pen to paper and outlining a broad vision and goals. Having those in place will help states identify systems, partners, and services that can contribute to the collective impact needed to achieve prevention goals. Once they have mapped potential partners, states can create actionable and realistic plans to engage with those agencies and organizations.

Engage early with a broad set of partners. States should engage with a wide range of agencies, such as those that oversee state services related to mental health, substance use disorders, public health, the juvenile court system, education, maternal and child health, and Medicaid. Some of the states and counties we interviewed also mentioned the involvement of county administrators; courts; parents’ attorneys; behavioral health providers; families, caregivers, and youth with lived experience; evaluators and university partners; tribal liaisons; and home visiting programs. By casting a wide net, states could learn more about the impact of current services and gaps in service delivery. Building those partnerships early could also be critical in ensuring that the key systems responsible for preventing maltreatment buy in to the upcoming changes and work together to plan a comprehensive array of prevention services.

Assess population and service needs. States must understand the landscape of need and the services that are available to moderate it. This includes identifying families with children who are at greater risk of entering foster care, the reasons they are at risk, the services they need to achieve greater stability, and which services are in place to meet those needs (if any). If states do not have needed services, it is important to consider how to build the infrastructure to provide them. Aligning the needs with the approved programs in the new federal Title IV-E Prevention Services Clearinghouse will allow states to match up evidence-based practices that can best fill gaps. Understanding Medicaid, other insurance coverage, or safety nets will help states determine the best way to pay for those services.

Determine priorities, goals, and actions. Once states understand the existing needs and services, there are multiple strategies they can take to pursue their goals. Some possibilities are improving linkages to insurance, services, or information; implementing and adapting evidence-based practices; and adding or changing coverage or funding. With their partners, states will want to think through the priorities and consider the best timeline for implementing changes.

Consider how funding aligns with these goals. Understanding the nuances of funding streams is key to any consideration of how to feasibly accomplish goals. States use a variety of funding streams to pay for mental health, substance use, and parenting programs, and Family First introduces an additional federal reimbursement option to cover the cost of some programs. By mapping out how they currently fund services, and including funding options they might not currently use, states can develop the best plan to meet their need for prevention services.

Develop the plan. States interested in Title IV-E reimbursement for prevention services must complete a five-year Title IV-E prevention program plan. In the plan, they must describe their services, lay out an evaluation strategy, and say how they will monitor child safety, coordinate services, support and train their workforce, shift caseloads, and report on prevention programming. The final part of the toolkit offers tips for creating a prevention plan.

States and counties undoubtedly have an exciting opportunity to keep more children safely within their own families, but they face complex challenges in implementing the changes set forth in Family First. We hope the toolkit illuminates a path forward for child welfare agencies and gives them some concrete steps to make the process more manageable.