This blog is part of our Growing the Evidence series, which contains evidence and insights uncovered by Mathematica’s researchers in the international food and agriculture sector.

By 2050, food demand is projected to grow by more than 50 percent, fueled by a growing global population that is expected to reach 9.8 billion in 2050. We also know that agriculture and land-use change produces about 12 gigatons of greenhouse gas emissions a year, nearly a quarter of all human-caused emissions. The main offenders are methane emissions from livestock production and rice cultivation, nitrous oxide from nitrogen fertilizer, and carbon dioxide released by fossil fuels used in agricultural production—all critical elements of current efforts to keep up with the growing global demand for food. None of this is sustainable.

To complicate matters, climate change influences agricultural yields. Floods, droughts, and increasing temperatures make farming difficult in some geographies, forcing farmers to clear forests for farmland, which contributes to the largest share of greenhouse gas emissions from the agriculture sector. In sub-Saharan Africa, the smallholder farming systems are the largest contributor to deforestation.

Food production depends on soil health, water availability, and other factors. Even so, compelling evidence shows that extensive food crop production systems common in sub-Saharan Africa negatively impact these environmental factors. Agriculture-related deforestation, soil erosion, water depletion, soil and water pollution, biodiversity loss, and climate change threaten the sustainability of agricultural systems. This interconnection between environmental and agricultural outcomes underscores the importance of promoting sustainable agriculture among smallholders across the globe, but more so in this region.

While there is broad recognition of the connection between agriculture and climate change, the majority of agriculture research efforts continue to focus primarily on increasing yields and do not typically measure the greenhouse gas implications of new technologies. Often, donor investments to improve agricultural outcomes can run counter to efforts to curb climate change. For instance, investments in irrigation infrastructure have increased in greenhouse gases as they brought additional land under rice cultivation during the dry season and causing an increase in methane emissions.

In recent years, donors have made investments to achieve the dual goals of agricultural productivity and positive environmental outcomes. But without a better understanding of how agricultural productivity and positive environmental outcomes can coexist, investment in such agricultural interventions might be doing more harm than good.

It doesn’t have to be that way. As we commemorate World Food Day 2020 and celebrate the 75th anniversary of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, those of us committed to addressing climate change can identify, study, and address adverse impacts through more sustainable agriculture interventions.

We already know that improving agriculture and livestock practices through managing manure, managing crop residue, and using nitrogen fertilizers efficiently can limit greenhouse gas emissions. So how can we incorporate these practices into our agricultural development work now and in the future?

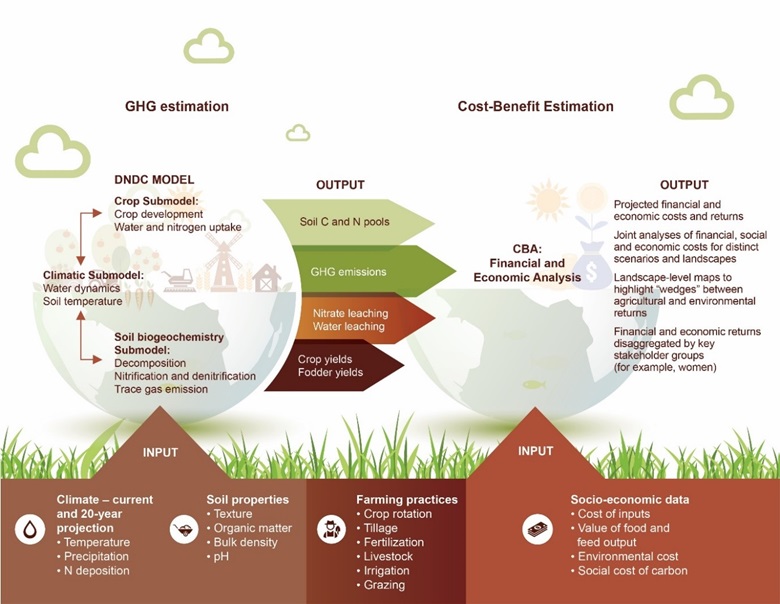

Through a co-creation workshop led by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), Mathematica co-conceived a decision support tool with Applied GeoSolutions, Senegalese Institute of Agricultural Research (ISRA) and Sustainable Intensification Innovation Labs to help donors and policymakers better plan for sustainable agriculture. The tool's input and output is illustrated above. This tool helps users apply a systematic approach to incorporating environmental sustainability into agriculture programs by analyzing alternative land management practices and systems, along with their implied land uses and commensurate impacts on greenhouse gas emissions. Doing so enables implementing organizations, researchers, and funders to not only estimate the expected long-term implications across key sectors, but also develop plans to address negative outcomes before they become engrained in otherwise promising practices.

Developing sustainable plans requires researchers to review current policies and engage a diverse set of stakeholders. This enables researchers to address the opportunities and challenges arising from the cross-sectoral impacts of agricultural projects. The decision support tool will help planners evaluate alternative scenarios of technology adoption and visualize their full financial, social, and economic costs, including impacts on greenhouse gas emissions and environmental and social outcomes. Finally, the tool will create a framework for monitoring the greenhouse gas emissions outcomes of these technologies to enable better mitigation strategies as the technologies are adopted and scaled.

In a field that has too often been measured by simplistic “win or lose” binary outcomes, our approach enables a much richer perspective on a wide variety of impacts across stakeholders—farmers, businesses, women, socially vulnerable groups, and governments. Taking a broader view with the support of this new tool deepens understanding of the social complexities of various options and identifies potential power conflicts.

Ultimately, we’re using this new tool to inform the scale-up of innovative agricultural technologies, particularly those that are developed after several years of in-country trials that typically generate information only on the technologies’ productivity impacts.

We’re already putting this approach into practice as a pilot project in Senegal to inform improvements in agricultural practices within large, interconnected networks and sectors. We are excited about the potential to build local capacity and ensure long-term success in Senegal by helping local leaders, implementing organizations, and funders use the tool, interpret results, and make more informed decisions about when to scale up sustainable agriculture technologies. Our first stakeholder workshop will be in November, 2020, and we will bring together scientists working at ISRA; farmers; extension agents; and leaders at the ministries of agriculture, livestock, and environment with the hope of forging connections across sectors. With ISRA leading, we will share details about the tool, gather feedback to make it useful to stakeholders, and conduct training sessions to make it easy to use. We expect to hand over the tool to the national agriculture research center in Senegal in 2022 to help them scale up sustainable agriculture interventions. Simultaneously, we are working with USAID to expand the tool’s use to other regions and countries, including a project focused on expanding sustainable cocoa in Ghana.

For too long, agricultural interventions have been narrowly focused on agricultural outcomes. But in today’s changing global economy, and with the current and future effects of climate change imperiling more aspects of our lives, we can’t afford to continue yesterday’s siloed approaches.